From page to stage to screen, how director Tom Hooper and DP Christopher Ross transmogrified the megamusical

“It’s completely barking mad, obviously,” says director of photography Christopher Ross, BSC of the first time he read the script for Cats. “The only way you can get some sense of the pace at which the songs take place is to read it while playing a recording of its Broadway run or of the play’s original London cast otherwise it reads like an enormous monologue.”

TS Eliot’s string of poetical whimsy from ‘Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats’ published in 1939 was an odd choice for a stage musical when it debuted in 1981 but Andrew Lloyd Webber’s interpretation became a record-breaking phenomenon.

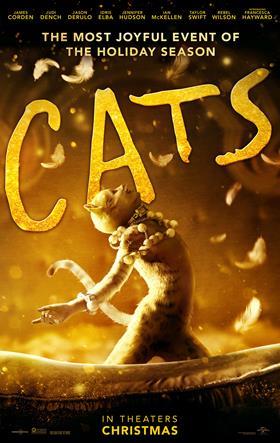

His Dark Materials’ director Tom Hooper, who delivered eight Oscar nominations for adapting Les Misérables for the screen in 2012, together with Billy Elliot and Rocketman writer Lee Hall, were deemed the purr-fect pair to bottle the magic for cinema in by Working Title’s star-studded U$95 million revival.

Hooper and Hall’s screenplay puts the character of Victoria (Francesca Haywood) front and centre and the film about her journey to become reborn with a second life.

“It’s a quite mind-boggling concept,” says Ross (whose last film, Yesterday, imagined a world without The Beatles). Why choose to do something bland when you can take on the challenge of creating something no-one has seen before?

His first conversations were influenced by the concept art drawn in watercolours by production designer (and Les Misérables alumna) Eve Stewart.

“We are in the world of London in the late 1920s and Soho is half derelict and half functioning and these cats effortlessly rule the territory around the back of strip clubs, theatreland, gentleman’s clubs and the smog-lined banks of the River Thames,” Ross explains.

In the Cats stage show, the felines are human sized. For his film, Hooper wanted to reduce them in size to the scale of the human world.

Read more Behind the scenes: His Dark Materials

“From the beginning he wanted to do as much in-camera as we could with real performers on real sets,” Ross says.

Leavesden Studio’s main Flight Shed soundstage was turned into a street with sets for Bustopher Jones’ junk bins, the moonlit graveyard scene of ‘Memory’, the neon-lit Milk Bar and the junk yard for ‘Jellicle Songs for Jellicle Cats’.

The set buildings ran to the full 30ft height of the stage. To give a sense of scale that’s only the first floor of a building in real life.

“We worked to give as clean a matt line as possible for VFX to extend the set above that height,” Ross says. “A curb was 18-inches high. A front door 24ft high.”

Sets featuring Trafalgar Square and Piccadilly Circus had CG backdrops since they would be too large to physically construct. He says, “In the world of a cat, the National Gallery is as far from Nelson’s Column as a mountain range is from a plateau”.

Trans-moggy-fy

The actors – including Judi Dench, Idris Elba, Rebel Wilson and Jennifer Hudson – wore lycra suits and tracking markers for VFX teams at MPC and Mill Film to apply digital fur.

The original show, of course, featured human performers in patterned lycra costumes, furry leg warmers and fur-based headpieces and gloves.

“Tom wanted this to look more deeply transformative – so we’re never really aware of the join between human and cat,” says Ross.

To transmogrify them, if you will.

Visually, Ross went deep into research on cinema musical history. He re-watched 42nd Street, West Side Story, Cabaret and All that Jazz. He took in Grease, Chicago, Mama Mia, and La La Land.

“I wanted to understand what it is that musicals do visually, how they have evolved and what aspects remain constant. Tom wanted to make that universality iconic.”

Music videos were an inspiration for the evolution of filmed dance movement: everything from Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ to Madonna’s ‘Vogue’, to Destiny’s Child, Beyonce, Dua Lipa and Childish Gambino.

“What often happens with dance on film is a repeat of the proscenium of a stage,” Ross observes. “This is more frequent in older musicals where they are replicating the theatrical experience in cinema but even some of the most joyful moments of The Greatest Showman and La La Land are shot in proscenium way. The reason is that it harks back to Gene Kelly in Singing in the Rain or Busby Berkeley’s chorus lines of Broadway Melody of 1936.”

Ross’ research also made him cognisant of the choreography of a dance and the spaces he could utilise on film.

“Seeing dancers photographed full body is counter intuitive when working in a musical form where the person who is dancing is often also singing,” he says. “You are frequently torn between two editorial choices. Also, choreography constantly changes the geometry of a shot. The physical shape of a person can change in relationship with others, perhaps performing identical moves or movements at counter point to them.”

Early colour photographs of Piccadilly and W1 provided information about the mood of Soho in the 1930s and the colour of gas lights. Films like Taxi Driver and One From the Heart were sources for the look of the street and neon signs.

Read more VFX: De-aging tech

Paws for scale

It was the scale of the piece, though, which provided most food for thought. Ross says, “There was a whole heap of math involved in working out how big a cat is in relation to our set. How big should it be when human performers have two legs and for the most part are standing, yet cats walk on all fours? How do you address that in scale?”

Clues were found in the way Pixar depicts the small humanoid characters of Toy Story with constant reminders that they are in a world that is too big for them.

“As soon as you do a close up of something that is either much bigger or smaller than it ought to be you quickly lose your frame of reference,” Ross says. “A face that fills the screen is just a human – not a cat. But if we constantly have something in frame that is oversize in relation to our cast it should be constant reminder to the audience that our humans are cats. It’s almost impossible to do in every shot but if we can do it half of the time we can keep the scale front of mind.”

The sense of scale flowed into camera choice and compositions. “We need to see the world from the cat’s perspective and one of the things that breaks that illusion is if the lens you are using distorts linear perspective. If you want to use a very wide angle the viewer will quickly realise that that their perception of reality has been altered.”

Using the large format ARRI Alexa 65 allowed Ross to shoot on wide lenses without the distorting depth cues. The main lenses were an ARRI Prime DNA set from 28mm to 150mm with a wide angle 21mm Signature Prime.

“Tom has quite a soft low contrast aesthetic so these lenses exhibit gentle fall off of focus. We were shooting at high resolution (6.5K Arriraw) so you could see imperfections in skin and therefore in the VFX so our lenses and lighting were intended to create a lovely smooth soft texture so you can see the fine detail in the cat’s fur.”

Ross also had to re-scale camera positions and moves that he’d make in conventional filming: “If we’re going to cover a scene using a crane we have to scale up that crane position.”

During a three-month rehearsal period, Ross and his camera team would sit in on the workshops, where Hooper and choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler were working with the cast, to get a sense of how they were using the spaces.

Most songs are filmed with a mix of Steadicam, tracking shots and cranes with the “more intimate visceral” songs such as ‘Mr. Mistoffelees’ switching to handheld for a first-person look.

“This is a story about a group of people who happen to be cats getting together once a year to choose who is most worthy to gain a second life. It’s got a cathartic, uplifting, and positive story behind it. Now it’s about to be released into the wild I hope that everyone has a great party with it.

No comments yet