Editor Chris King and director Asif Kapadia tackle Argentina’s footballing enigma, Diego Maradona, in this documentary which comes to DVD this month

To a heart-pumping electro-synth soundtrack and in grainy handheld video you are jumped straight into the front seat of car riding at pace with Diego Maradona. The city is Naples, the destination the Stadio San Paolo and this opening sequence to the biopic of the footballer – which comes to DVD this month - is noisy, chaotic and cut like a chase scene.

“This crazy drive seemed to sum up his life and the footage is all jump cut in this crazy French Connection style,” says director Asif Kapadia.

-

Read more: Craft Leaders: Asif Kapadia, director

Diego Maradona is the subject of Kapadia’s latest archive driven study of larger than life personalities which follows the hugely successful Senna (2010) and Amy (2015) and is once again a collaboration with editor Chris King.

“We had researchers make a huge sweep of existing material from broadcasters in Italy and from Boca Juniors [Diego’s first club] and we also had access to a large number of tapes filmed by Diego’s own camera crew,” King says. “That was the hook that got us into the project.”

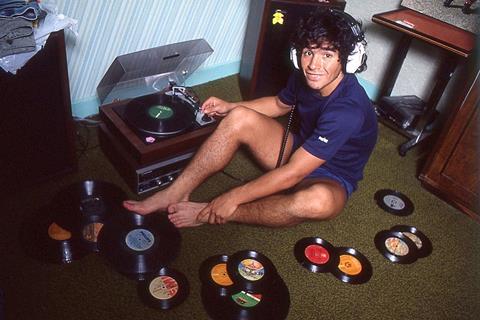

This personal archive had been commissioned by Jorge Cyterszpiler, Maradona’s agent, who shot hundreds of hours of candid footage on U-matic video between 1981 and 1987 of his charge relaxed at home, partying in clubs, travelling in planes, training and on the pitch.

“This was material that even hardcore Neopolitan fans hadn’t seen,” Kapadia says. “It’s not like it was all kept together and neatly archived. There was a hard drive full of footage we found in Naples and someone else had tapes in a trunk in Buenos Aires that hadn’t been opened for 30 years.”

The best example of this is a scene showing the moment Maradona walked into the Napoli stadium for first time. “The shots taken from behind him as he walks up the stairs to the pitch were found in Naples; the reverse shot was on a in tape in Buenos Aires,” Kapadia reveals.

King boarded the project in early 2017 after much of the initial research has been done. “We had an optimistic plan to get it ready for just after the World Cup 2018 but it got mired and we got caught up in the drama in the cutting room.”

Golden boy

Diego has lived his life in the media gaze. The pressure to perform in public is part of the film’s thesis. In the film, his little boy lost ‘Diego’ persona is contrasted with the pompous drug-fuelled Hyde of ‘Maradona’ who must show no weakness.

“He’d lived five lives before he even set foot in Naples,” King says.

Their first step was “to bolt together a rough timeline of his life, make some intuitive guesses, eliminate obvious duplication, and react to the material.”

Viewing 500 hours of raw material took two to three weeks alone.

“Asif creates his own timelines of 9, 10, 12 hours long on his Avid and I’d make my own selections on the other side of the room,” King says. “There was a huge amount of stuff to wade through.

“My initial take was that all his life is fascinating, chaotic, clamorous from the get-go. There’s no serenity at all. A single year of Diego’s life was a decade of anyone else’s – in their wildest dreams. We couldn’t possibly show it all.”

It became apparent that all roads led to Naples and Maradona’s seven years playing for SSC Napoli as the defining moments for this story – arguably of his life.

“That the most famous, most talented and most valuable footballer in the world went to an unfancied part of Italy, signed to a low ranked unfashionable club, raised questions which we thought we could try and answer in the rest of the film,” King says.

But to tell the story of Naples, they had to understand what had brought him there.

“The centrepiece was Naples but that would only work if we felt happy that we’d understood what came before,” Kapadia says. “The heart of the story only emerged after two years of trying and failing and trying again.”

The deal the film’s producers had struck with Maradona included securing his image rights and access to his personal video archive. In addition, they had contracted for a series of three three-hour interviews.

“In reality his attention span would wander after about 90 minutes,” says Kapadia who visited Maradona at his home on one of the Palm islands in Dubai. “I said, ‘let’s leave it today and come back tomorrow’. When I came back, I’d be lucky if I got maybe two hours total.”

To interview other witnesses for the film, including Diego’s personal trainer during the Naples period, Kapadia travelled to Buenos Aires and Barcelona.

“Our budget was only so much that we could afford a trip every 8-10 months. Many people have tried to pin down who Diego Maradona is but it’s challenging. He comes with a bit of an entourage and he’s also quite strong character. No one would talk to us unless he gave them the OK.”

“Half-angel, half-devil”

The interviews with Maradona themselves were so patchy and unrevealing that the filmmakers considered not using them at all.

“They were a bit vague and just a kind of familiar version of stories he had already told,” King says. “He launched into a lot of anecdotes that we’d already seen in other material. He was definitely not going near the more contentious areas of his life. He didn’t answer some of the questions put to him.”

Probing into his cocaine habit, which began in Barcelona and continued at pace in Italy, was brushed aside by a pat statement “as if he were in a press conference rather than in any detail,” King says.

In addition to which the way Maradona spoke was “quite slurred or tired…maybe he was on medication. It was difficult to understand him. There was quite a low energy to the recording.”

Senna and Amy may have lacked a first person narrative but with Maradona “we felt we’d lost the immediacy of those films.”

It wasn’t a complete disaster. “Of the chaos of arriving in Naples we got the sense that he didn’t really understand what was going on around him. He explained his reasons for going there were financial as much as anything but that he felt compelled to go.”

Naples was the only club prepared to finance his wages and pay the then world record transfer fee of £6.9 million.

“When he did say something illuminating or funny we felt with the right kind of audio trimming and sound mix it could be pepped up. There was a temptation not to use it all, but it did offer a different dimension to the other films.”

King says Maradona’s time at Barcelona was particularly difficult. “He felt racially diminished as a South American in the city. His wife did too.”

His calamitous time in Spain included a shocking leg breaking tackle by Athletic Bilbao defender Andoni Goikoetxea and an incredible on the field brawl with the same player which ended Maradona’s Barca career.

All that, plus his childhood growing up in a Buenos Aires slum, his introduction to Europe’s club scene and experience at the 1978 World Cup, took up the opening 45 minutes of the film but ended up condensed to 5 minutes and intercut with footage of his mad arrival by car to Napoli’s stadium.

“Post Naples we had a really powerful 30 minutes as well but this version was four hours long so we had some really tough decisions to make,” Kapadia says.

With five weeks until picture lock the opening sequence was “elegiac, slow, quiet, melancholic” explains King. “We realised we were making the same mistake we’d made with Senna and Amy. We’re signposting at the beginning that it’s going to have a tragic end and it didn’t reflect the youthful energy that Diego had at that time. The music was working counter to the footage.”

Sound of God

Inspired by the Giorgio Moroder-style disco that Maradona would have been partying to in Naples during the eighties, King replaced the score for the title opening with the track ‘Delorean Dynamite’ by Todd Terje.

“It pumped it up much more and underlined that all these events are inexorably leading toward this fateful encounter in Naples.”

He then rescored the first half the film using more electronic music and 80s-90s synth electro to keep the same energic feel. “As the film darkened in the second half we bring in [composer] Anthony Pinto’s score more and more until it dominates.”

As one might expect, much of Maradona’s story is told using footage of him playing but sports production in the mid-to late eighties was in the pre-Sky dark ages.

“It wasn’t like now where you have 50 cameras trained on the pitch with a dedicated super-slow mo picking him out of the crowd,” Kapadia says. “The broadcast footage was mostly from the high gantry position which we used once but didn’t capture any close-up action. Fortunately, his personal crew were able to follow up onto the touchline and behind the goals.”

King talks of trying to emulate the violence with which football was played at the time. “It was a contact sport. We wanted to undo a decade of TV innovation and get it back to showing a bunch of tough men running around, clattering into each other, interspersed with moments of unbelievable skill of Maradona threading his way through physical assault.”

The audio that accompanied the football footage, however, was very weak. Any official broadcast had loud Italian commentary all over it, which is used occasionally, but for the most part all the sound had to be stripped sound out and rebuilt in the edit.

“The audio is equal to the picture in terms of the amount of work,” King says. “Every tackle, every shot, every run and tumble is a bit of foley I’ve added in to create something authentic and of the period. The whole thing is a huge artifice in one way or another.”

The mosaic style which Kapadia and King have pioneered eschews talking heads and came about by accident, says King, when making Senna.

“Asif had recorded interviews with a few people on a handheld mic just for research and the intention of using it as a signpost for building the story but when we listened back it was mesmeric. He felt he didn’t want to break the momentum of the film archive by cutting to a modern interview. It would take you out of the moment. So that meant we had to find a style and the one we used was drama fiction with spare bits of audio to guide us through.”

The documentary convention of the time typically had an explanatory talking head followed by archive b-roll footage to illustrate what had just been said.

“For us the b-roll is the A-roll,” King says. “The film is the archive. Asif is genius at watching what appears to be something relatively banal and understanding that when shown on a big screen with sound it becomes this dramatic moment.”

A clip in the film shows Diego in a bowling alley. Its footage from the collection of a Napoli Ultra (hardcore fan) who had befriended Diego at the start of his time in the city.

“There’s a fear and vulnerability in Diego’s eyes as if he realises what Naples is going to mean to his life,” King says. “Asif saw that and used it and you wouldn’t do that if you were producing a more conventional doc. He is crediting the audience with a lot more intelligence to read the film.”

King and Kapadia’s treatment of the picture is layered. Some official match replays of Maradona’s goals were only available in slow-motion. King sped them up 150 per cent to run at normal speed. Footage is frequently panned and scanned from the original TV standard 4:3 to 1:85 widescreen, retimed and colour corrected.

“I use lots of blur to subtly draw your eyes to Diego while the rest of the picture is out of focus,” he says.

The rough and ready look to the film is deliberate to evoke the period. “We initially grab in all the material [digitise it] for assembly edits and when we go back to get the masters we spent a bit of money on standard conversion or re-telecineing original pieces of film. The technical post is huge.”

At time of release, Maradona still hadn’t seen the film.

“I’m still owed an interview by him,” Kapadia says. “I held one set of our three interviews back until I had the final film to show him assuming he would want to comment on what happened or say that this or that didn’t happen. Every time we tried to show him, he was too busy. He was in Colombia or Mexico or Moscow for the World Cup. We tried really hard to show him the film.”

They toyed with adding a coda about his life and appearance today. “There’s already enough material out there. It was unnecessary,” King says.

Despite the unprecedented access, the real Diego Maradona remains an enigma. “He was born in this rough, rough place on the outskirts of Buenos Aires and he feels that no-one gave a shit about him when he was living in real poverty and only gave a shit once he was rich and famous,” Kapadia says. “He’s saying ‘you can’t judge me’ because you don’t understand me. He may live in a gilded cage, but it’s a cage nonetheless.”

No comments yet