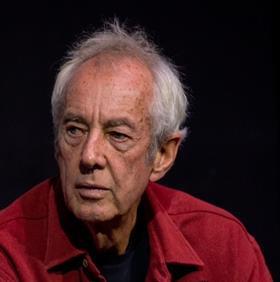

When Edward Norton wanted to convey the loneliness of life in 1950s New York for his noir feature Motherless Brooklyn he turned to cinematographer Dick Pope, BSC.

Dick Pope, who is Mike Leigh’s regular collaborator behind the camera from Life is Sweet to Peterloo, jumped at the chance to photograph a film noir for director Edward Norton.

“It’s a dream for any cinematographer to be asked to recreate fifties New York with all the visual flourishes of a noir,” Pope says of Motherless Brooklyn, which Norton wrote, produced, stars in and directed.

- Read more: Craft Leader: Edward Norton

“I was brought up on noir film. My father idolised noir actors of that era and was a number one fan of Dick Powell (whose Philip Marlowe in 1944’s Farewell My Lovely is considered definitive). That’s why he called me Richard.”

Motherless Brooklyn is an adaptation of a bestselling novel by Jonathan Lethem about a private detective in New York investigating a murder and uncovering corruption. The twist is that the central character has Tourette’s, which manifests in head twitches and odd vocabulary but a knack for joining the dots in a puzzle.

The last thing Pope wanted was to pastiche the genre. “Shooting black and white wasn’t a consideration. Ed wanted it to have a patina of old cinema but not to look like there was any special treatment to it. We weren’t copycatting noir films. This New York had its own set of parameters.”

“I could view the whole virtual scene on a tablet on set and make decisions about camera placement and lens choice.” – Dick Pope

Rather than cinema, Pope poured over street photography of the era as well as pictures of Brooklyn and Harlem.

“From the Hopper paintings we took notes on composition, from the photography it was the feel of them - particularly about the tone of light. For instance, I was really enamoured by a photo of the original Penn Station, a fantastic building with a vaulted glass ceiling and sunlight pouring down into the concourse. I took that as the basis for designing the lighting for our Penn Station.”

While the film is a mix of studio and location work, the background set for scenes at Penn Station – torn down and replaced in 1963 - are largely VFX.

“We had props – benches, lockers, a concourse and people - but everything was against bluescreen,” Pope explains.

He was able to visualise how any shot would look with a pre-vized panorama of the Station devised by VFX supervisor Mark Russell. “I could view the whole virtual scene on a tablet on set and make decisions about camera placement and lens choice.”

He shot with dual Arri Alexas using Cooke Panchro/i Classics “to combat the digital and give it more of a period feel” - a similar combination to the one he deployed on Leigh’s Mr Turner.

A pivotal scene near the film’s beginning attempts to gives the audience a visual insight into the mechanics of a mind working with Tourette’s. In it, Frank Minna (Bruce Willis) holds a conversation in a dark room while Lionel (Norton) waits outside at a payphone listening in.

“One thing Edward Norton wouldn’t do is compromise. He wanted to see the film he had lived with as he originally planned it”- Dick Pope

Pope shoots it in a diffused, soft-focus way as if from Lionel’s filtered perspective.

“It’s what Lionel thinks what’s happening in the room that is important. It has a slightly otherworld surrealistic collection of images which were the nearest to black and white we came in the film. We used rigs for both cameras suspended on bungee straps from the ceiling to give it a handheld feel whilst blurring in and out of focus. Hopefully, the viewer feels as blocked out as Lionel feels.”

Pope first met the actor on the set of The Illusionist in 2006, a film for which Pope was Academy Award nominated.

“We hit it off and after that experience, we stayed in touch,” Pope says. “All those years later he contacted me about shooting his film. It’s a labour of love for him.”

He says that he and Norton went through the film shot by shot so that when they got to set the actor was able to concentrate on his performance.

“One thing he wouldn’t do is compromise. He wanted to see the film he had lived with as he originally planned it. He’s quite right about being determined to get what he intended onto screen. I think he got the film he wanted.”

- Read more: Behind the scenes: 6 Underground

No comments yet