The rise of the streaming platforms has sparked a production boom, affecting superindie groups through to smaller indies. It has had a major impact on all genres of programme making too - and the way that shows are now financed. Tim Dams reports.

There’s a global battle underway right now for the very best content - and the key beneficiaries are producers.

Additional money has poured into programme making thanks to the investment of SVOD platforms such as Netflix and Amazon on standout content to attract paying subscribers, with Netflix alone expected to invest $15 billion this year. This has been boosted by the likes of Disney, Apple and Quibi who are prepping their own streaming services, investing heavily in an array of shows. Short-form service Quibi, for example, is armed with a $1bn content budget.

- Read more: Can Quibi crack the short form market?

Digital players such as Facebook, YouTube and Snapchat are also investing in content, while niche AVOD and SVOD services around the world are hungry for library content.

“At the moment, there’s a production boom that doesn’t look like it is going to end anytime soon,” says Guy Bisson, research director at Ampere Analysis. “It has been hugely positive for the production landscape…it is a great time to be a producer and to own content.”

The impact of this production boom has been felt right across the sector, affecting superindie groups through to smaller indies. It has had a major impact on all genres of programme making too, and the way that shows are now financed.

“There’s a production boom that doesn’t look like it is going to end anytime soon,” Guy Bisson, Ampere Analysis.

The growth in scripted content is the most obvious stand out feature of the new production landscape, with some 500 new dramas airing each year in the US alone.

The demand for ambitious, complex and talent-filled dramas has changed the nature of scripted production – raising the stakes for those involved in making them. Claire Hungate, the former CEO of Brave Bison and Warner Bros Television Production UK, and guest chair of the 2019 IBC Conference, notes that the average cost of a scripted hour was £750k seven years ago, before the SVOD boom, and now stands at £1.5-2m. “The scale of these shows is now so huge that the skills you need from your team are completely different, as is the time it takes to set them up and the risk profile of the shows.”

Hungate says there is a now a question as to whether a low-cost drama model might make a return. She notes that SVODs are moving away from co-producing big budget drama with traditional broadcasters. “Does the UK have to move back to a lower priced model where we can produce drama for between £500k - £750k an hour?,” she asks.

“The scale of these shows is now so huge that the skills you need from your team are completely different” Claire Hungate

While drama has grabbed all the headlines, the unscripted sector is incredibly vibrant, adds Lucas Green, the head of content at superindie Banijay. “Unscripted has almost come up on the inside while the whole world is looking at the big budgets the streamers are spending on drama,” he says. “It’s also lower risk, cheaper and much quicker to produce.”

Off-script

Netflix, for example, has started commissioning more unscripted content, including game show Flinch and cooking competition The Final Table, having also enjoyed success with fact ent series Queer Eye through to natural history series Our Planet.

Green also points to commissions for Banijay-owned Bunim-Murray Productions from Facebook Watch (a reboot of reality format The Real World) and Snapchat (docu-series Endless Summer.) Meanwhile, Banijay-owned formats like Temptation Island are being rebooted by terrestrial broadcasters in territories such as the US, Germany and Australia.

“We see this war between platforms both old and new as an opportunity for us as a producer,” says Green.

Similarly, rival superindie group All3Media has taken advantage of the rise of the SVODs.

“We see this war between platforms both old and new as an opportunity for us as a producer” Lucas Green, Banijay

All3Media CEO Jane Turton says Netflix and Amazon “have been huge” in terms of their impact on the business. All3Media owned production companies have picked up a string of commission from the streamers: Amazon, for example, partnered with the BBC to finance Two Brothers Pictures’ Fleabag, and with ITV on The Widow. Netflix, meanwhile, has backed Lime Pictures’ Free Rein.

The demand is not just in drama. All3Media-owned Raw TV has won a raft of non-scripted orders from Netflix, which has also ordered reality format The Circle from All3Media’s Studio Lambert.

The streamers, she says, have also helped to fund genres that were previously struggling, particularly kids’ drama, sci-fi and comedy. The latter, in particular, has had a renaissance thanks to the streamers, having been seen as too expensive and high risk by many traditional broadcasters.

Growing demand

The growing demand for content has had all sorts of knock on effects, right across genres. “There are challenges with access to talent along the whole value chain from writers to producers to actors, through to studio facilities and post production,” says Ampere’s Guy Bisson.

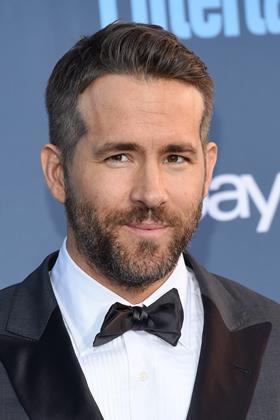

This demand for talent spans both scripted and non-scripted. The number of A list actors moving from film to drama has been well documented, as streamers seek top talent to make their scripted shows stand out. The same is true in non-scripted too: “If you are expecting someone to stay with you and binge watch a format, you really have to have top notch talent in it, both to keep the viewer with you and to help cut through with marketing,” says Banijay’s Lucas Green. He cites Deadpool star Ryan Reynolds making family game show Don’t for US network ABC, through Banijay Studios North America.

Green says that the reality of today’s production market favours large groups like Banijay. “You need to have that size as a group which allows you to broker strong deals and remain robust in the market place.”

It’s a point echoed by All3Media’s Jane Turton, who says “scale does matter.” That, she explains, is largely because the business of television is now much more complex than it used to be, amid huge change in viewing habits, rights deals and budgets.

IP value

At a time when their content can now be seen multiple times on multiple platforms, producers have to be more sophisticated than ever in the deals they strike with PSBs, US networks, cable companies and SVODs. With co-productions, deficit funding and tax breaks all now in the mix as well, Turton says that companies with a big portfolio of shows are well placed to work out the best model for a production deal. A larger company like All3Media can also help get a show off the ground by providing deficit financing – and manage the risk of doing so across its portfolio.

The rise of streaming platforms has also thrown attention on the value of IP as never before.

Netflix, in particular, has started producing content in-house – and looks set to do so even more, having bought or long-term leased studio space around the world, most recently at Shepperton Studios.

Netflix also looks to take all rights to projects it commissions from producers, the logic being that it wants to be able to release its content on its global platform without worrying about rights payments.

As a result, the indie sector is “moving back to a work for hire model”, says Claire Hungate.

She wonders if the production sector may shift towards a packaging model, with individual producers, writers and/or directors packaging projects and taking them to Netflix for the streamer to produce itself. This may suit individuals and smaller production companies who don’t want to take on the risk of producing such big budget projects themselves. But it is likely to be resisted by the larger, more powerful production groups.

Traditionally, the advantage of producing for hire for Netflix is that it paid a big premium on top of budgets to buyout international rights. But these are reportedly reducing.

Tom Harrington, senior research analyst at Enders Analysis, says there are dangers for producers given the growing power of a just a few SVOD services who aren’t bound by terms of trade with producers. “There is a fear that Netflix’s growing market power could create a situation where independent producers just become “producers for hire” who get no IP - which is usually the case now - but also the margin they make on their production costs is squeezed more and more. Netflix will also take more work in-house.”

The fact that streamers are looking to hold on to IP could prove a key trump card for traditional public service broadcasters who allow producers more generous rights deals.

In the UK, Channel 4 recently agreed a new rights deal with producers, with the broadcaster relinquishing its share of secondary international revenues in return for greater freedom to exploit programmes across its platforms in the UK.

“The thing we are most interested in,” says All3Media’s Jane Turton, is commissions from PSBs – the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 which come with Terms of Trade, allowing it to hold on to programme rights. “That helps us to create the IP and launch it around the world…it’s the best version we can ever dream of for a programme commission.”

- Read more: What next for IP?

Interested in programme making? Attend Is there a future for linear broadcasters? at IBC2019 on 14 September.

No comments yet