In the latest of our Industry Innovators series looking at those who have had a major impact on the media and broadcast industry, IBC365 speaks with Garrett Brown, the inventor of Steadicam.

It all started on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The iconic scene from Rocky has been paid homage to or parodied dozens of times and is rehearsed daily by tourists on what is now known as the Rocky steps - all thanks to Garrett Brown.

The shot he took of his wife Ellen in 1975 running up the steps was a showcase for the invention of a camera stabiliser that has arguably had a more profound effect on camera movement than any other technology.

The Steadicam freed the camera from being bound to cranes and the straight lines of dolly tracks. Instead, the camera could be moved handheld but smoothly for entirely new shots around corners, through doorways, travelling up, down and in any direction. Using it, cinematographers began to transform the rigid language of cinema with complex and fluid compositions.

The Oscar-nominated 1917, filmed as if in one unedited shot, is just the latest motion picture to be inspired by the near half century-old mechanical design which shows no sign of being superseded in the age of digital.

- Read more: Behind the scenes: 1917

“Steadicam remains the most artfully controllable means for moving a camera,” Brown tells IBC365. “For filmmakers who cherish expressive moving shots, it is the go-to technology — principally because Steadicam shots most closely resemble what humans see through our remarkably-stabilised eyeballs as we navigate our own daily ‘movies’.”

New romantic

Brown is first and foremost an inventor though he has always cherished the movies. His affinity with both is romantic. As a child in the 1940s, he recalls the cover of a book in which “the sky was filled with dirigibles, propeller planes and autogyros,” and the foreground with great ‘Streamliner’ locomotives, sleek racing roadsters and motorcycles.

“I dreamed of inventing as a kid and wished to have my name on an ‘apparatus’,” he says. “It’s tragic that we don’t encourage young people to be inventors. We encourage them to be technical and to be engineers, but we don’t romance the idea of invention.”

Perhaps because of this, he left school “with no job skills” and learned about cinema by reading “all the outdated film books” in the central Philadelphia library.

He tried folk singing, agency copywriting, “despairingly” selling Volkswagens, and eventually directed some commercials, finally buying a job-lot of old camera equipment for $1000 which he intended to rent. This included an 800lb dolly called the ‘Fearless Panoram’ which was needed for moving a Bolex camera.

Fed up with how cumbersome the gear was to use, and especially how hard it was to lay level tracks, he determined to do something about it.

“I had the idea for how it should work and had done enough experimenting to have an instinct for what had to happen,” he says of the four-year trial and error. “Other people assisted me in building it. Each version taught me more about what the next one should be like.”

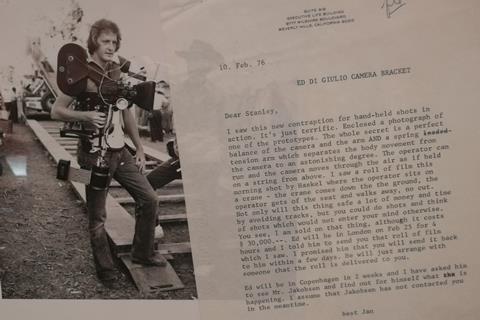

The demo reel titled Impossible Shots featuring the Philly steps sequence found its way to John Alvidsen, director of a low budget boxing movie starring little known actor Sylvestor Stallone, but the ‘Brown Stabilizer’ had already been used on Marathon Man and Bound for Glory. All three films released within a few months of each other in 1976 and Brown and his newly christened Steadicam were suddenly Hollywood’s hottest property.

Dexterous operation

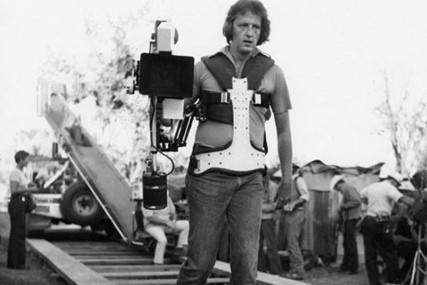

Building the rig was one thing, operating it quite another. Use requires a dexterity that is easily underestimated, necessitating intermittent severe effort alongside a surprising delicacy of touch. Brown likens its particular combination of art and athleticism to playing a musical instrument.

“It’s like simultaneously moving and playing a piano,” he says. “Both operate at the ‘human/machine’ intersection, both respond to training and practice, and success with either is idea-driven rather than just physical.”

For this reason, he says, “tiny women are among the best operators, and big muscle-bound blokes may initially be among the worst.”

He elaborates: “I’ve always enjoyed thinking about the performing arc of a successful shot in comparison to the arc of great musical performance. Neither good Steadicam nor pleasing music are boringly continuous - they breathe with the life of their driving ideas, subtly retarding and advancing pace.”

This is analogous to Rubato, an expressive shaping of the tempo of classical music, he suggests. “It is the ‘robbing’ of time by slowing and catching up which can be emotionally involving.”

Another musical notation, Sforzando, or sudden loudness, can evoke sharp accelerations within moving shots. “The problem isn’t playing any one note, it’s sustaining a succession of them and setting yourself up for the next one.”

Steadicam expertise often begins with one of the workshops organised by the Steadicam Operators Association he founded in 1988.

The Shining to Jedi

Brown himself has produced some of the most renowned Steadicam moves in cinema, operating for directors (and their cinematographers) including Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Francis Coppola, Warren Beatty and Tony Scott.

He wielded the camera around the corridors and maze of the Overlook Hotel for Stanley Kubrick giving an oily sheen to The Shining. He tracked Robert De Niro’s Jake La Motta from dressing room to the ring in Raging Bull. On Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Brown operated on the rope bridge in Sri Lanka.

“A diabolical set, since it was shockingly real,” he recalls. “300 feet above the river, plunging up and down when anyone moved, with actual six-inch gaps between boards, and all conducted in humid 100-degree heat.”

Highlander remains a sore point. He executed a flawless opening Skycam shot in 35mm, but according to Brown, “the producer inexplicably, refused to pay us and skipped town. I had to sue him to get my dough. And they used my shot!”

One two-minute shot in Casino is among his favourites. De Niro’s character narrates how casino’s handle the money from front of house to the cash-counters in backrooms.

“Documentary-like agility was required in the counting room as the extras appeared unpredictably far from their marks every time I entered the room and then wandered about like gerbils throughout the shot.”

He also shot the background plates for the speeder-bikes sequence in Return of the Jedi by strolling precisely through a redwood forest with the camera turning at .75 fps. “To make that work, I kept the corner of my matte box aligned with a stretched 1000ft green thread as I moved, and I cornered and panned very slowly as [vfx supervisor] Dennis Muren operated my roll-cage at 1/30th speed.”

Played back at normal speed and comped with bluescreen of bikes and actors the tour-de-force was “pleasingly realistic” since the Steadicam shots contained some “camera-car-like vibrations” which George Lucas felt gave the scene additional energy.

Though cameras have shrunk, the ‘vests’ now more comfortable, the monitors incalculably better and the materials lighter and stiffer, all four or the original requirements to build a Steadicam remain essential: expand the mass so that the centre of gravity of the camera pops out from inside the camera like a seesaw, access the centre of balance with a gimbal, support it all with a ‘floating’ arm and provide a remote look through the finder.

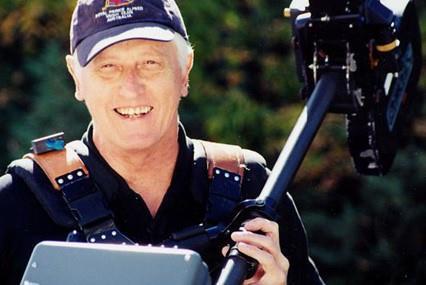

Steadicam was just the beginning of his inventions. Brown holds 50 patents mostly for camera support systems. These include SkyCam, the first suspended flying camera system, variants of which are now ubiquitous at major sports events; and Flycam, another wire-borne system invented to provide an overhead view of Pope John Paul’s visit to Mexico in 1979.

- Read more: Industry Innovators: Bill Warner, Avid

MobyCam, the first submarine tracking camera system debuted at the 1992 Summer Olympics. Vertical camera tracking system DiveCam was custom-invented for the 1996 Atlanta Games.

There have also been several iterations of Steadicam the latest being ‘Volt’, a technology that improves horizon and tilt control.

“For years we were obliged to operate with the Steadicam slightly bottom-heavy in order to feedback an idea of verticality when looking away,” Brown says. “The Volt permits operating in neutral balance, which means that level and tilt angle are automatically maintained and we can finally just concentrate on the essentials of great shooting.”

His favourite invention was not a commercial success. Tango is a miniature crane perched on a Steadicam arm that permits floor-to-ceiling shooting and smooth ‘traverses.’

“In the old days I used to take out all of my camera inventions and shoot movies with them to jump-start their success,” he says. “Since I retired from shooting in 2004, unhappily there has been no champion for Tango. I’m confident it will be revived eventually. It’s too exciting and is huge fun to operate.”

Brown was honoured with an Academy Award in 1978 for developing Steadicam and received another Academy Award for Scientific and Technical Achievement for SkyCam, in 2006.

He’s the first to admit that business acumen is not his forte: making money was never a motivation.

“I wasn’t smart enough to somehow tie each use of Steadicam to a buck or two of royalties,” he says. “The first patent for Steadicam expired in 1994 but subsequent patents have remained valuable.”

Brown would argue that no-one outside of the industry should ever notice a Steadicam shot. Just like any other technical aspect of production, it shouldn’t call attention to itself. He is ambivalent about so-called ‘one-ers’ – films composed entirely of unbroken sequences “unless both sensible and valuable.

“Filmmakers can now digitally stitch together shots that give the illusion of continuity across any imaginable barrier, but it [can suggest] that the camera has no more substance than a neutron or a quark, and the result is correspondingly trivial. There is something about the massy, klutzy dolly and crane shots in old movies that resonates. Something physical. They felt more important, more meaningful.”

Brown once began to describe his profession as ‘inventor’, “since neither my cinematographic nor directorial chops were ever world-class”, but decades of mockery as eccentric nerds in comic books and films like Back to the Future, put him off. Lately, however, inventors seem to be back in fashion.

“That’s all I’ve done for years, so ‘Inventor’ it is and will be!”

No comments yet