In the first of three articles on global broadband access, billionaire and visionary Elon Musk has a plan to supply a global satellite system for the planet’s ever-hungry broadband connectivity.

PayPal co-founder Elon Musk has skillfully converted his 11.7% share of the online payment system, sold in 2002 to eBay for $1.5bn, into a “multi-billionaire” fortune.

In October this year, Forbes said he is now comfortably worth more than $20 billion, and the 21st wealthiest person in the US.

He is the genius behind the Tesla range of electric cars – and now trucks. He wants high-speed inter-city travel connections via his HyperLoop technology (the “Boring Company”) and his SolarCity projects, as well as battery-powered jet travel.

The 46-year-old has also created SpaceX, a rocket company that has revolutionised the way satellites - and eventually humans - are launched into space and which is posing a very real economic threat to the France-backed Arianespace system.

And Musk is also moving rapidly ahead with a scheme to launch 11,000 satellites into Low Earth Orbit (LEO), with the first being launched in 2018.

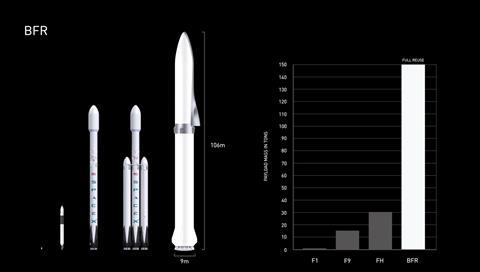

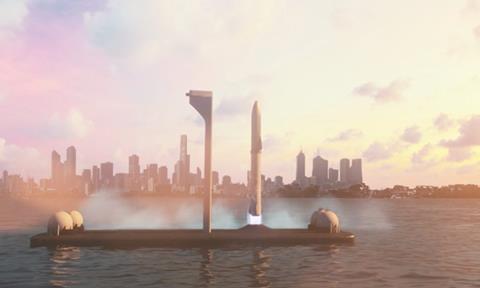

By the way, he wants to build a truly giant rocket (which he has cheekily christened the BFR for “Big Fucking Rocket”) for a Mars colonisation project, and which might also be used to ferry passengers between places such as New York to Shanghai in 39 minutes, and anywhere on Earth to any other place in under an hour – provided there was a place to land the beast.

Despite some criticism over the slow pace of deliveries for his Tesla electric cars, one by-product is a very successful line in rechargeable giant ‘Power Pack’ Lithium-Ion batteries for towns and cities, and one unit supplied to the city of Adelaide in Australia in just 94 days in Autumn 2017.

In other words, Musk is managing to convert many of his ideas into hard cash. Moreover, many of the ideas are useful in more than one of his projects: his Tesla cars helped create the battery projects; the SpaceX rocket has led to low-cost satellite launches for NASA and commercial satellite operators and hence the proposed global mega-constellation of LEO craft.

Musk’s ambition is considerable. He has stated that his ‘Starlink’ 11,000+ satellite system could handle up to 50% of all backhaul communications traffic and up to 10% of local internet traffic in high-density urban areas.

- Musk is managing to convert many of his ideas into hard cash

- 39% of Americans living in rural areas lack any sort of access to meaningful advanced telecoms connectivity

- SpaceX sees the first 800 LEO satellites deployed will enable the system to provide initial US and international coverage for broadband services

He opened the SpaceX satellite R&D facility in Redmond, near Seattle, in January 2015.

There are two separate schemes: the first is for 4,425 satellites to girdle the Earth, with the first test satellites orbiting in 2018 and then to be populated with regular flights in 2019 and to reach full capacity by 2024 – and working for consumers in 83 orbital planes at just 1110-1325 kms high, and with traffic latency of just 25-35 milliseconds – meaning that transmission would be ultra-fast and rivalling fibre.

The second scheme calls for an additional 7,518 satellites working in the – as yet – unexploited V-band (40-75 GHz), and extremely close to the ground at 335-346 kms (in Very Low Earth Orbit – VLEO), and with even speedier latency.

“These assets,” says SpaceX, “would enhance capacity where it may be needed most, enabling the provision of high speed, high bandwidth, low latency broadband services that are truly competitive with terrestrial alternatives.”

Both schemes need to overcome some in-orbit challenges, not least ensuring they do not interfere with transmissions from traditional very high-flying geostationary TV satellites. “SpaceX anticipates that the first 800 LEO satellites deployed will enable the system to provide initial US and international coverage for broadband services. Deployment of the remainder of that constellation will complete coverage and add capacity around the world.

The VLEO Constellation will add enhanced capacity where demand may be greatest, and satellite enhancements derived from lower power demand and more compact spot size will add user value without increasing system costs,” says SpaceX in its official Federal Communications Commission (FCC) filing.

But SpaceX is far from alone in wanting to exploit V-band connectivity. Boeing, OneWeb, Telesat, SES/O3b and Theia each has plans for their own constellations of satellites.

Potentially V-band transmissions – which can be highly focused - could supply multi-Gigabit/second traffic to the user, or to ground-based hubs.

The SpaceX LEO satellites will each stay in orbit for about 5-7 years, and then burn up in the atmosphere about 1 year after they have been switched off. The VLEO craft will naturally de-orbit within a few weeks of the end of their working lives, says SpaceX.

Musk’s team say that deployment of the first 800 satellites in the LEO constellation will permit widespread US and international coverage sufficient to offer commercial broadband service.

Completion of the 53º inclination orbit will add capacity throughout the system and provide robust broadband connectivity around the globe, with service concentrated in the area between 60 deg. North Latitude and 60 deg. South Latitude.

SpaceX says that broadband demand is already in place, and growing exponentially. “Internet protocol (“IP”) traffic surpassed the zettabyte threshold in 2016 – meaning over 1,000 billion gigabytes of data exchanged worldwide. By 2020, that figure is projected to more than double (reaching a level nearly 100 times greater than the global IP traffic in 2005), global fixed broadband speeds will near-double, and the number of devices connected to IP networks will be three times the global population,” according to its FCC filing.

Moreover, SpaceX says that despite the proliferation of claimed high-speed internet the reality is that some 39% of Americans living in rural areas lack any sort of access to meaningful advanced telecoms connectivity, and that one in ten Americans have no access to 25 MB/s broadband.

“Today, 4.2 billion people (or 57% of the world’s population) are offline for a wide range of reasons, but often also because the necessary connectivity is not present or not affordable,” says SpaceX, quoting the United Nations Broadband Commission.

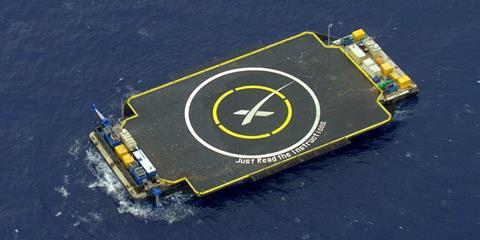

Launching these satellites is not a challenge for SpaceX. On October 9, 2017, SpaceX delivered the 3rd batch of 10 small satellites for Iridium. An on-board dispenser successfully ejected the satellites using a Falcon 9 rocket from its California launch complex at the Vandenberg Air Force base. Iridium has a contract in place with SpaceX to launch a total of 81 of its satellites.

Musk is already developing a ‘Falcon Heavy’ rocket, capable of much larger cargos and with two sets of ‘strap-on’ boosters.

Indeed, in November 2017 he raised another $100 million to help finance development costs (and in the process valuing SpaceX at a reported $21 billion). But his BFR is in a very different class. Its 31 ‘Raptor’ reusable engines can carry 150 tonnes of payload into LEO. Its main fuselage would be as wide as an Airbus 380 aircraft (9 metres) and could be sub-divided into 40 separate crew cabins.

Engine testing is already taking place. Construction of the first BFR is due to start in Q2/2018, and a trip to Mars is planned for 2022. The core design calls for complete reusability of the rocket.

Musk has a habit of simply getting things done. His ‘basic’ Falcon 9 rocket is winning order after order, simply because it is cheaper than its rivals and proving to be extremely reliable. Do not underestimate his ability to pull off his 11,000 satellite project, or his BFR rocket.

No comments yet