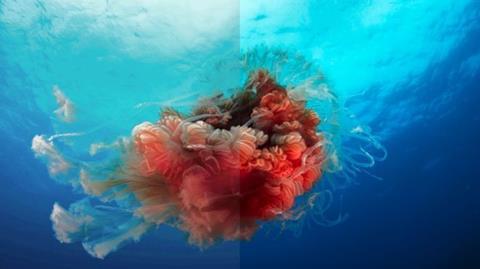

The availability of BBC natural history series Blue Planet II in UHD HDR has been one of the more high profile recent HDR releases, but have the variety of industry standards and approaches hampered rollout?

Not so long ago ITU-R WP 6C gave us a suite of standards consisting of Hybrid Log-Gamma plus Dolby Perceptual Quantisation.

They were very different tool sets, but they would take us from camera to the promised land of the smart TV.

HLG was meant to be compatible for legacy connections. PQ 10 was static metadata, but offered a wide range of brightness levels.

Move onto Dolby Vision with its 10,000-nit brightness capability and impressive colour range, with the continuing presence of the Philips/Technicolor system, and people started to sense that the reach of HDR services to the consumer market was stalling because there were too many protagonists.

And then Samsung - supported by Amazon, 20th Century Fox and Panasonic - introduced the royalty-free HDR10+ with its dynamic metadata (tone mapping).

This enables less clipping of HDR content: an extra layer offering scene-by-scene information to enable smart TVs to better handle the playback of HDR.

“The industry is generally concerned that the lack of a clear end-to-end proposition is stalling the deployment of HDR services” - Peter MacAvock

Samsung also stressed the uniform experience across TV consumption that HDR10+ seems to offer, and claimed it is easier to use in mastering. Expect extra consortium support, and further technical enhancements.

Dolby Vision and its smart TV hardware chip have been the empire striking back successfully for a long time, but the consortium that quickly appeared behind HDR10+ is no trivial happening because it suggests that the big content peddlers are getting frustrated. They know that the best consumer HDR experience is the one closest to how the content was shot and mastered, but that consortium did not want to be hamstrung by royalties.

At IBC2017 the issues around this subject were the different HDR systems/standards, the support for HDR in consumer devices, and the levels of metadata that broadcasters would have to invest in.

Read more HD HDR has more wow factor than Ultra HD

Straight after the show DVB chairman Peter MacAvock observed: “In the DVB Project, we are considering how to proceed here, and I’m wondering whether we leave our solution as it is, or whether we are more aggressive in seeking harmonisation between the proponent dynamic metadata systems. It’s a tough one.

“In the background, the industry is generally concerned that the lack of a clear end-to-end proposition is stalling the deployment of HDR services - to the detriment of us all,” he added.

For the Digital Television Group (DTG), Peter Sellar, Associate Director Broadcast, said: “A lot of manufacturers are deploying HDR in products, although they may not all be deploying the same HDR. And content providers are putting stuff out there; Netflix for one, and the BBC is doing some HDR and will be doing more.

“It is going to take time for everyone to do it, and you need to see a critical mass of viewers before starting to roll out the content,” he added.

“Manufacturers now seem to have multiple versions of HDR supported in their products. We have gone past the point where people were asking who is going to use it, and how they are going to use it, and it is being deployed.”

Sellar made the points that the different standards have different attributes, and that HLG and PQ is where we have stood so far. Set makers already support more than one HDR standard.

“Then there is HDR10+ as well, and this has opened up another discussion around Dolby Vision,” he said.

Grass Valley’s Mike Cronk, VP of Core Technologies, provided a broadcast industry vendor perspective. He said: “We are seeing a strong uptick in the number and frequency of HDR trials. We support a comprehensive native HDR live production workflow from camera to production switcher and multi-viewing with HDR/SDR up/down mapping to support the transition.

“We also support HDR in our playout workflows,” he added. “We are flexible and support either PQ or HLG, and in that sense they are somewhat immune to how the distribution to consumer battle plays out.

“Broadcasters can produce HDR today, and the numerous trials are designed to hone the workflows.”

Delivering Blue Planet II in UHD HDR

For the BBC’s second UHD trial the broadcaster has made all seven episodes of Blue Planet II available in UHD and HDR. It follows a UHD HDR trial last year in which technologies including Hybrid-Log Gamma, a version of HDR the BBC invented with NHK to address the needs of broadcasters, and DVB-DASH (PDF), an open-standard for Internet streaming, were tested.

The BBC R&D team explained in a blog post that “although not as complex as delivering a linear broadcast channel, getting UHD HDR content onto BBC iPlayer still presents significant challenges”.

It explained that the UHD version of the series was post-produced in HLG HDR, “so we did not need to convert between HDR formats to get it onto BBC iPlayer. “However, we still needed to HEVC encode seven one hour UHD programmes - with each programme taking about a day to encode. This is because we need to create up to 11 different versions at different image resolutions, meaning we can target different bandwidth internet connections.”

ITU-R WP 6C was chaired by Andy Quested, technology strategy and architecture, BBC Design & Engineering.

He said: “Life is easy. All these options seem to miss the point that there is an HDR system that simply works end-to-end but seems to be ignored at the moment. Why is this? What’s odd is there are still only two ways to exchange HDR content internationally; other than BT.2100, all others are just ‘local agreements’ for one-off events.”

Everyone gets a trophy

Matthew Goldman, Senior VP Technology, TV & Media, Media Solutions, Ericsson, discussed the multiple issues at play.

Asked if it is fair to say that HDR comes in too many varieties he said: “Unfortunately, this is true. Not just for the consumer, but rather for the entire ecosystem, from production, through distribution and onto the consumer.

“Many of us in the professional media industry have tried to reduce the options by working within standards development organisations and industry forums both to urge the selection of a best-in-class solution – or at least a minimal set – and to see whether the proponents of the many different proposed systems could come together to form a ‘grand alliance’.”

The appetite to make this happen appears to be absent, which Goldman believes to be surprising.

“No HDR method currently being offered is truly backward compatible to legacy equipment” - Matthew Goldman

“The raison d’être of an SDO is to foster interoperability by selecting ‘one tool for one function’ whenever possible from a set of many proposals,” he said. “This has proven to be a successful strategy throughout major advances in our industry, which brings to mind the question what is an SDO role if it adopts all methods presented before it?

“This ‘everyone gets a trophy’ environment already has resulted in a delay in HDR implementation, according to several content and service providers/operators. With the above in mind, equipment providers – both professional and consumer – have to make a trade-off between implementation complexity and the risk of making an incorrect choice for what the market decides over time,” he added.

Backwards compatibility with SDR looks like a red herring, but it was part of the logic behind Hybrid Log-Gamma as matched to Dolby PQ as a standard.

“No HDR method currently being offered is truly backward compatible to legacy equipment - legacy being the hundreds of millions of non-HDR displays in use today. While Rec. ITU-R BT.2100 the HLG transfer function is backward compatible to the standard dynamic range gamma function (BT.709/BT.1886), the colour gamut used in UHD is BT.2020, which is not compatible with legacy displays,” said Goldman.

“Before HLG can be displayed on an SDR legacy display an external colour gamut conversion function must be performed,” he added.

“The so-called SL-HDR1 is also not backward compatible to legacy displays when video compression is deployed, which for direct-to-consumer applications is always in the workflow, because to preserve HDR fidelity, 10-bit sample depths are required and legacy devices are all 8-bit.”

Goldman moved onto the bonus of better brightness.He said: “It is true that by its nature the PQ transfer function (SMPTE ST 2084 and ITU-R BT.2100) includes more headroom for highlights, so any implementation using PQ, whether HDR10, Dolby Vision, Technicolor/Philips SL-HDR1, Samsung HDR10+, etc, would incorporate the same headroom.

“The concepts behind the HLG and PQ transfer functions view the use of highlights differently and which is the better option is a serious ‘religious’ argument,” he added.

With regard to the lack of a clear end-to-end proposition and whether this is stalling the deployment of HDR services Goldman’s answer is a yes with reservations.

“The real answer is more complicated. We should keep in mind that HDR standards and specifications are still relatively new, so there has been much progress in the offering of end-to-end propositions even since IBC,” he said.

“However, I do believe that end-to-end HDR propositions would have been available earlier had the industry coalesced around a single – or fewer HDR schemes,” he added.

“One of the missing pieces that applies across the HDR ecosystems is the inclusion of HDR signaling and metadata in both SDI standards (SMPTE) and HDMI. Standardisation is almost complete in this area and this will aid greatly in enabling standards-based end-to-end HDR offerings.”

Viewing distance and bandwidth

Has the notion of adding HDR to 1080p, seen at the Ericsson NAB booth three years back, faded away now? Perhaps the way HDR anticipation has sped up UHD take up made it a good but dead idea?

“4K-image resolution requires about four times the bandwidth of HD” - Matthew Goldman

“Absolutely not,” said Goldman. “Many content and service providers/operators are considering transmitting/delivering 1080p HDR as the source format.”

He said that two issues are driving this. The first is viewing distance in relation to display size.

“Resolving spatial resolution is highly dependent on both of these factors. A good rule-of-thumb is that, in order to resolve 4K resolution fully, the viewer needs to be located about 1.5 times the display picture-height from the display, while with HD, the proper viewing location is about three times the picture-height,” he said.

“For most home viewing environments today, consumers are sitting between 2.5-3 times picture-height back from the display.

Bandwidth usage is the second consideration. Goldman said: “4K-image resolution requires about four times the bandwidth of HD in baseband (uncompressed) and circa 2-2.5 times the relative bandwidth for direct-to-consumer compressed bitrates.

“This is a significant difference when bandwidth constraints exist, such as with digital terrestrial TV transmissions and some streaming over Internet applications.

“HDR - actually, by HDR what is really meant is HDR plus wide colour gamut plus 10-bit sample bit depths, used together - does not have these strict viewing conditions, nor does it require anywhere near as much additional bandwidth,” he added.

“For example, in the compressed domain, the extra bits required for HDR could be 0-20% more than the equivalent SDR version. Clearly, the best viewing experience is possible when the resolution of 4K is combined with HDR. However, for some applications – taking into account viewing distance and bandwidth – 1080p HDR is the best bang for the bit because much of the perceived Ultra-HD viewing experience can be achieved with this format.”

No one is suggesting that 1080p HDR displays will come on to the market.

“The economics of producing 4K HDR displays is not the issue here; it’s the transmission/delivered format. All 4K displays have excellent up-converters and will seamlessly up-convert 1080p to 2160p,” Goldman concluded. “Unless the standards development bodies and forums change their approach to identifying HDR, then this will be left to the market to decide over time.”

Too early for compromise

Wolgang Lempp, the founder and CEO of the grading tool specialist Filmlight, acknowledged that his company has been a member of a loose European HDR project, along with Arri and BARCO, for the past two years. The purpose has been to get an understanding of HDR, without the ambition of driving any new standards initiative.

He said: “That project is small compared to the big beasts of the industry.”

With regard to Matthew Goldman’s comment about everyone getting a trophy he said: “That is a fair statement. The fact that SMPTE (and the ITU) have standardised a whole range of HDR technologies is an indication of the amount of money involved. Because of that people won’t step aside or abandon their own technology for what somebody else has developed.

“Whatever is thrown at us, we have to make it available. That’s just a reality, and we can only react to what is happening there,” he added. “It is not possible to create multi versions and multiple protocols because nobody is going to pay for that. Something needs to happen.”

Lempp would like a time out, and for things and be simplified, but there is a but. “With standards bodies, who has the time to sit there for month after month? It is the big boys and they will sit there to protect their commercial interests,” he said.

“I cannot see a compromise, but in two or three years the commercial battle will play out and you will get winners and losers, and people will have to bend. Sadly it is too early yet for them to give up and compromise.”

2 Readers' comments