Editing films is “very instinctual”, says Oscar winning editor Lee Smith

From sound design on The Piano to co-creating the intoxicating long opening shot of Spectre and manipulating the space/time puzzles of Christopher Nolan, few editors have as astonishing a track record as Lee Smith ACE.

Nominated for three Oscars (winning one for Dunkirk) and with credits including The Truman Show, Elysium, X-Men: First Class and Inception, the 59-year old is in constant demand.

“Editing is very instinctual,” Smith told Editfest, an event organised by the American Cinema Editors guild for an audience of peers, aspiring editors and assistant editors at the BFI. “The physical mechanics of cutting two shots together can be trained and learned but it doesn’t necessarily make you any good. The choices are far more important – the rhythm, the application of music and the sound effects. Everything needs to come together.”

The Australian started out as a sound editor then sound supervisor for Antipodean directors on films like Dead Calm for Peter Weir, Lorenzo’s Oil for Mad Max director George Miller and The Portrait of a Lady for Jane Campion.

“The mechanics of cutting two shots together can be trained and learned but it doesn’t necessarily make you any good. The choices are far more important.”

“My father was an optical effects supervisor, my uncle ran a small optical lab, my aunt was a neg cutter and my brother an animator, so I guess I didn’t have a choice,” the editor explains.

His first industry job was in a “very small post house” in Sydney doing animation, feature film and docs where he gravitated toward the audio department.

“I realised that to be a good picture editor your knowledge of sound is very important. You need the technical ability to lay sound into the Avid because that will help your final cut.

But film is the sum of its parts. One part does not work without the others.”

The first of three notable relationships with directors was with Weir. “I started working for him when I was a kid really and worked my way up through the ranks of the editing team,” he says cutting The Year of Living Dangerously (as associate editor), Fearless and The Truman Show.

“Some directors rely on storyboards and arrive on set with a very accurate plan of what they will shoot. Peter just responds to what he sees on the set and will change tack on the day when he realises something it is not working. His process is organic.”

Smith say he turned down Peter Jackson’s invite to edit The Lord of the Rings to work with Weir on Master and Commander: Far Side of the World (2003) the Napoleonic-era seafaring saga starring Russell Crowe, which landed Smith his first Oscar nomination.

For one dialogue heavy dinner party scene set in the captain’s cabin, Weir had exposed 25,000 ft of 35mm negative.

“It was a lengthy sequence with a lot of characters and coverage [angles]. You had to sift through a fortune of material and try to stay true to the sequence which is really about Hornblower connecting with his crew. In any other director’s hands this might not have been much of a scene, but Peter succeeds in showing the bond between the characters. That’s important because you want the audience to want to be on that boat and then feel the tragedy when half of them are killed.”

The Nolan years

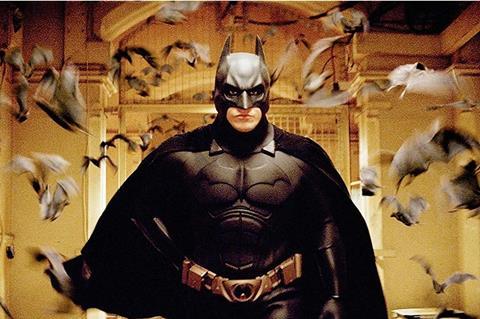

The Oscar nod opened more doors including to Christopher Nolan who needed someone to edit a reboot of Batman. Initially Smith resisted the offer to edit Batman Begins because he says he didn’t want to work on a superhero movie.

“When I met Chris, he persuaded me that he was going to treat the subject with a great level of seriousness,” says Smith. “He had answers for everything.”

The film effectively birthed a whole subgenre of superhero origins movies and by extension, the later Marvel and DC franchises.

Its follow up, The Dark Knight, was darker still since it features the intense and, tragically, last film performance of Heath Ledger as the Joker.

“I’d edited one of Heath’s first films [Two Hands] in Australia when he was just a kid and I kind of couldn’t believe they were even considering casting him as the Joker. When I watched the first day of dailies it was a shot on a street corner with Heath standing there with a clown mask before getting into an SUV but he has his back to camera the whole time. It was extraordinary. He owned the screen just by the way he stood.”

Other collaborations with Nolan include The Prestige, The Dark Knight Rises, Inception and Interstellar although Smith admits, only half joking, not to entirely understand Inception or “whatever was going on in the bookcase sequence” in Interstellar.

“You have to be interested in puzzles and deconstruction and reconstruction to work on Chris’ films,” Smith says. “The scripts that he writes with his brother [Jonathan Nolan] are like a watch. You can mess with it, but it still has to tell time on the other end.”

Nolan’s films typically contain multiple timelines and in Interstellar’s case at least one other dimension, but none were as complicated to assemble as Dunkirk.

“We have the hour, day, week triple timeline of parallel stories told in the air, the land and the sea that has to converge and then separate again,” Smith says. “We had some leeway over the point of convergence. This is where the armada of boats from England arrive on the scene and there’s a huge rush of emotion because until that point the film has been unrelentingly tense. It was vitally important to gauge when that scene would drop.

- Read more: Maryann Brandon: Editing with emotion

“The driving idea behind Dunkirk was how could we make a film tense from the split second it opens, to drop the audience into what would be third act in any normal film, but we also had to know when to ease off, when to deliver that catharsis.”

In order to present the multiple timelines in a chronology which an audience would understand, Smith explains that he would take the entirety of sequences related to air, land and sea and stitch them together and play them back linearly.

“The trickiest timeline was the aerial one which had the least amount of screen time but in early versions we found we were still getting lost. By pulling all the footage out and bolting it together you could get an overview to help weave it into the other two thirds of the story.”

In contrast to Weir, Nolan “has precision knowledge of how he is going to shoot and cut,” Smith says. “The edit is built into to how he shoots. He knows what he wants and gets what he wants.”

Don’t flog a dead horse

The third of Smith’s serial collaborations is with Sam Mendes. They are currently in production together on period drama 1917 which, by its pedigree alone (cinematography is by Roger Deakins), is tipped for next year’s Academy Awards.

“He will abandon a scene on set if he intuitively feels it’s not working,” Smith says of Mendes, citing an example from Spectre. “He’s right not to waste effort flogging a dead horse but doing that requires conviction and the budget to back it up. The problem is usually in the script.”

The celebrated opening of Spectre - set during a day of the dead parade in Zócalo Square, Mexico City - is a complicated sequence involving multiple subliminal cuts to appear as a seamless shot. It cleverly masks exterior and interior set-ups filmed in the city, other Mexican locations and Pinewood.

“You gain experience with every film. And if the DNA of a film is simply not in place then there’s nothing much you can do.”

“We had 17 cameras running during the sequence shooting from every conceivable angle and all shooting film. It took me eight hours just to watch the dailies. Chris Nolan on the other hand is very frugal with his coverage - perhaps because he shoots a lot of IMAX film which is very expensive stuff.”

Smith is not doing Nolan’s next film, Tenet, which is currently being shot with Jennifer Lame (Hereditary) in the cutting room. This was simply a matter of scheduling which clashed with 1917.

“When you are presented with a film that is happening, greenlit and ready to go right now then I think you should say yes rather than wait for a director you also want to work with but whose film is waiting to be financed,” he explains. “There’s always the risk that films can be pushed back. It might eventually put you out of sync with those you want to work with, and the decision is never taken lightly but you have to work - editors also need to get paid.”

Generously, his advice for editors looking for their big break was that everything they do, regardless of the outcome, counts.

“You don’t work any less hard on an also-ran movie than on a cinematic masterpiece,” Smith says. “You gain experience with every film. And if the DNA of a film is simply not in place then there’s nothing much you can do.”

- Read more: Craft leaders: Adam Gough, Editor

No comments yet