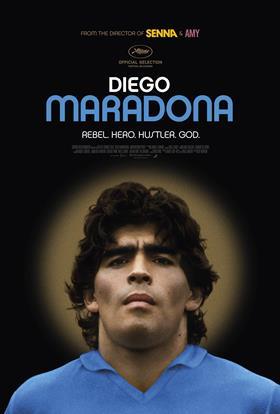

In his latest documentary, director Asif Kapadia unearths the complex and sympathetic man behind the enigmatic Argentine football legend.

At one point in the new film about his life, Diego Maradona says: “I played football because I didn’t want to return to Villa Fiorito.”

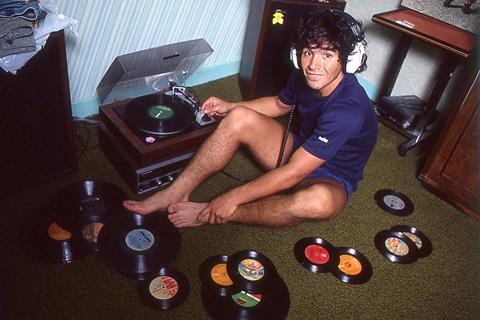

The documentary suggests that the intensity of his battles on the pitch, and the insecurities he exhibited in a chaotic life off it, was forged in the poverty of the Buenos Aires shantytown where he grew up and the subsequent sudden shock of his superstardom.

“People only remember the latter version of Maradona, his deceit, his drug problems, his obesity,” says director Asif Kapadia. “They forget how incredible he was. They think they know him, but they do not. That’s what this film sets out to reveal and confront.”

Sport biopics are not new to Kapadia, nor are talented but flawed and tragic subjects. His previous documentary features, Senna, about Brazilian racing driver Ayrton Senna, and Amy, about the late singer-songwriter Amy Winehouse, share similarities with Kapadia’s treatment of the 60-year old ex-footballer.

Tabloid journalism has turned the Argentine into both genius and pariah, but Kapadia unearths a more complex, sympathetic but still enigmatic character.

“There’s a bit of Senna and Amy in Diego,” says Kapadia, who travelled to Dubai to interview him on several occasions. “Like Senna, he is a Latin American hero of the people. Like Amy, I don’t think he’s ever been able to feel comfortable in his own skin. For whatever reason it got to the point with both that even when things were going well, they would push away the people who cared for them. It’s linked to their addiction, but it’s also linked to being a child star.”

Subverting documentaries

The Londoner has spent four years, on and off, making the film although the idea came from a book he’d read long before making his first documentary.

“I wanted to test myself with somebody who is still around and to tell a different type of story about what happens when you get older if you’re a star.”

Personal challenge is important to Kapadia’s own motivation. His graduation short from the Royal College of Art, Sheep Thief, was shot on 16mm using a non-professional cast in Rajasthan. It won multiple awards.

His first feature The Warrior (2001) was shot in the Himalayas and desert regions of India and in Hindi, winning the BAFTA for Best British Film. Next, he went to the Arctic tundra to shoot Far North, a psychological drama starring Sean Bean and Michelle Yeoh.

“I wanted to test myself with somebody who is still around and to tell a different type of story”

In contrast to director Paul Greengrass, who has taken his background in documentaries into gritty dramas ripped from the headlines (United 93; 22 July), Kapadia made the switch from fiction to documentary “intentionally to subvert the genre” by treating real-life stories like a drama.

This included ditching the customary talking heads and narrative voiceover for a more intimate approach that managed to tap into the vulnerability of his personality. Senna’s depiction of the Brazilian’s fate is almost spiritual.

Amy, on the hand, became a musical. He says: “My family background is in India and Bollywood films use songs to tell narrative. Clearly Amy is not here to talk to, but we do have her songs and her lyrics which are very personal and in the film, they become her voice to help us understand what was going on in her head.”

Of the switch from drama to documentary, Kapadia explains that he went through “a mid-life, existential crisis” between ten and 15 years ago when he realised he’d fallen out of love with fiction and with the process of making it.

“I’d spent all my life watching and working on drama,” he explains. “Making one was the gold standard, everything I’d aimed for, but I just wasn’t being engaged any more. I felt that most movies I saw were just pretending to tell incredible stories.”

True fiction

Kapadia says his interest in film had always been in the cinema of Japan and Asia, France and Italy but that his own attempts at ‘world cinema’, like The Warrior, had been tough.

“Without making a film in the English language and without a major star you just cannot get incredible stories with big characters financed,” he says. “I guess I sat down one day and realised that there are incredible, powerful stories about huge characters waiting to be told that didn’t require the pretence of fiction. Amy, Aryton… there’s nothing formulaic about their lives. These are characters who lived their lives in ways that just couldn’t be made up.”

Even better, the material to tell their story was already out there.

“With Senna, everything was free to view on YouTube. Anyone could have seen the footage. There were fans in France and Brazil asking what a Brit is going to tell us about Aryton – until they saw the film. We managed to take all these materials, we did the looking and we showed his amazing life in a way that hadn’t been done before.”

The mix of archive pictures overlaid with mostly contemporary audio from interviews conducted by Kapadia is styled as “true fiction”.

“One of the things I find frustrating about drama is that the process can somehow kill spontaneity,” he says. “It can lock you down to what you want to say but with documentary, I can be investigative and journalistic.”

“One frustrating thing about drama is that the process can kill spontaneity”

He continues, “I begin by doing a lot of research. I look at footage, read books, throw the net as wide as I can to find out everything about a character. Only after a year or two of the writing process do we start to find what looks like a story. We’ll do interviews which often throws up more questions. We’re constantly asking what we can show; how can we tell an idea. It’s very organic and evolved. Also, I like to change my mind and start again which is entirely contrary to how you would direct fiction.”

There’s criticism of the documentary conventions which preceded Senna. “The personal experience of the documentary maker on the subject matter - their voiced narration, sometimes their filmed presence, often distracts from the story. I wanted to treat [the subject matter] like a movie and find a way to present it so the audience could form their own idea.”

Kaleidoscope of picture and sound

That sentiment goes double for Diego Maradona who has been the subject of countless video articles, highlights reels and documentaries including a feature by Emir Kusturica which The Guardian dubbed a “fawning biopic”.

“Diego is a tricky character but the journey to making a film about him often becomes the film. I wasn’t interested in that at all.”

Kapadia’s style is also to use a kaleidoscope of picture and sound manipulation. He studied graphic design before film and the influence shows.

“I was at a show on print making and pop art at the Hayward Gallery last year and it popped into my head that essentially what we are doing is like [Andy] Warhol: taking footage and making something else with it,” he says.

“Essentially what we are doing is like Andy Warhol: taking footage and making something else with it”

“We’re taking material and zooming or panning into it, altering its colour, slowing it down, adding text and music, clipping dialogue, taking interviews from here and there to create a new interpretation which, I hope, is somehow more aesthetic, more political, deeper, emotional.”

After Amy became the UK’s most successful documentary with earnings in excess of $25 million, Kapadia had his pick of projects. Through On the Corner Films, the production company he runs with producer James Gay-Rees, he exec produced another football doc about troubled Brazilian striker Ronaldo; a retrospective look back at Oasis (Supersonic) and last year’s hard hitting three part examination of police inaction following the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence.

He has also returned to fiction, directing Ali and Nino, an adaptation of a classic romantic novel set in Azerbaijan, and two episodes of Netflix serial killer series Mindhunter for showrunner David Fincher.

A bio-doc of boxer Mike Tyson is rumoured and would make an obviously juicy next target for Kapadia’s attention.

“I am interested in taking not particular likeable characters and humanising them,” he says. You’ve got to have interest in humanising them but without passing your own judgement. I guess if someone were to run a line through my work all the way from the Royal College of Art to today you might suggest they are about outsiders. One of my tutors at film school made that observation but it’s not something I’ve consciously thought about.”

His trilogy of documentaries is about talent brutally short-circuited by the system. If Senna, in Kapadia’s film, was the tragedy of one man versus the commercial machine, Winehouse is portrayed as a working-class hero whose wings were burned by the media. Maradona, for all his faults - including a drug compromised relationship with the Camorra - is fighting demons not always of his own making.

Where Amy controversially suggested that Winehouse’s spiral downwards could have been suspended by her family, it’s clear from Diego Maradona that his parents were nothing if not supportive.

“Diego left home very early,” adds Kapadia. “He’s been searching for a home ever since. Just the fact of where I had to travel - Barcelona, Dubai, Argentina and Italy - in order to catch up with him shows that he never stays in one place for long.

“Really, the place that was closest to home was Naples.”

- Read more: Craft Leaders: Robert Richardson, Cinematographer

- Read more: The key to live content? Make sure it works

No comments yet