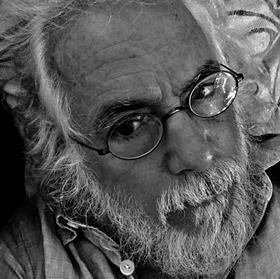

Three-time Oscar winning DoP Robert Richardson reflects on a career that has spanned 30 years, working with directors such as Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Oliver Stone – and working in formats ranging from digital 3D to ultra-wide 70mm.

There are few more hot-bloodied or revered auteurs in the last thirty years of cinema than Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino so it must take a cool head to be the eyes for them all.

“I will always put the director and the story first. That does not make producers overly happy but I don’t know another way,” says Robert Richardson, ASC.

His extraordinary career has seen him craft nine films with Stone, five with Scorsese and five for Tarantino and counting. He’s experimented with everything from digital 3D to an ultra-wide 70mm format, landed three Oscars including for JFK, The Aviator and Hugo, and is the DP to whom Robert De Niro, Ben Affleck and Andy Serkis turned to compose their directorial features (The Good Shepherd, Live By Night, Breathe).

“At the beginning I was raw - now I offer experience,” he says. “I believe I understand how to tell a story.”

With his latest film, A Private War, he has come full circle with his first film, Salvador. Based on events leading to the murder in Syria of venerated war correspondent Marie Colvin, A Private War is documentary filmmaker Matthew Heineman’s narrative debut. Salvador (1986) is a polemic of Reagan-era Central America conflicts through the lens of gonzo journalist Richard Boyle (James Woods). It still retains its venom.

The power of the story

“I do feel I’m returning to my roots on this project,” says Richardson of Heineman’s film. “The subject matter aligns quite remarkably [with Salvador]. Both are low budget and both are essentially documentary in style. Of course, I felt blessed to have been asked to make Salvador but now I have the choice.

“In this case, Marie Colvin was a monumental inspiration, her influence is incalculable. In addition, Matt’s clear willingness to make this film does not hold back on the truth – Syria, in particular, where genocide continues. He is an extremely focused and honest filmmaker which is rare. Very rare.”

It is the chance to shoot a good picture rather than a good-looking picture which fires Richardson up.

“I began making movies at a time when the subject material was vital, and with directors who dealt with material that meant something,” he explains. “I’m drawn to their work and I’ve been incredibly fortunate to work with them.”

With Stone he shot Platoon, Wall Street, The Doors, Born on the Fourth of July and Nixon. For John Sayles, Richardson shot Eight Men Out about an infamous baseball match fixing scandal while the Errol Morris documentary Standard Operating Procedure concerned Iraq’s notorious Abu Ghraib prison.

“Today, the subject matter for major pictures is less vital than its commercial potential,” he says, sadly.

“I don’t ever want to stay the same. I believe technology and technique and advances in everything from cameras to projectors are there to be used to tell the story.”

Pioneering style

Richardson’s search for challenging material is reflected in an adventurous style that has seen him play with acquisition materials, visual textures, and aspect ratios to achieve the right emotional resonance for the story.

“I don’t ever want to stay the same. I believe technology and technique and advances in everything from cameras to projectors are there to be used to tell the story.”

Hugo remains one of the few mainstream films shot with dual cameras and a mirror to provide the parallax. “It’s creating true 3D as opposed to a post conversion,” he says.

The manic visual palette of Stone’s Natural Born Killers mixed 8mm, 16mm, 35mm colour and black and white with Betacam video, rear projection and double exposures to mimic the impression of someone flicking between channels or to alternate subjective viewpoints.

“The choice of format shifted depending upon the sequence and sometimes altered within a sequence to provide editorial alternatives to texture,” he explains.

For Errol Morris’ Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, Richardson employed a similar fusion of formats as well as Super 8 film, stock footage and cartoons to create an impressionistic collage of images.

Then for Kill Bill, his first film with Tarantino, Richardson duplicated footage over and over again until it attained the texture of old Kung Fu movies for one scene; shooting the whole film (and its sequel) with snap zooms, stylised lighting, and lurid colours in reference to the exploitation movies the director wanted to evoke.

Later when Tarantino wanted to release The Hateful Eight as a 70mm movie, Richardson captured the film’s super-widescreen images with Ultra Panavision 70 lenses that hadn’t been used since 1966’s Khartoum.

“I’m currently shooting film for Quentin on Once Upon a Time In Hollywood. He loves film, as do I, because there is a beauty to it, particularly in the way it captures skin tones. But for me, if film dies as a medium then so be it. Everything is ultimately released on digital today anyway. The Hateful Eight was shot on film, graded on film and released on digital but Quentin couldn’t care less since he wanted to make a special release on 70mm in theatres.”

He stresses: “I have no issues with new technologies. In fact, I search them out.”

On Affleck’s 1920’s gangster picture Live by Night, Richardson shot some scenes at 2000 ASA on an Arri Alexa 65, sensitivity to low light near impossible with negative film. Similarly, sequences depicting Homs in A Private War were lit solely with flashlights, random street lamps or street fires and very little else.

“I shot at 1600 ASA (on Arri Alexa Mini) with Zeiss Super Speeds and used standard light bulbs on strings to give additional light where necessary. It was far more minimal than I generally work with but this is the direction the future will take as digital capture improves in both range and fidelity of skin tone.”

He is also keen to experiment with high speed cinematography, an aesthetic explored by directors Peter Jackson and Ang Lee but which has yet to find either an audience or the right story.

“I met with Ang Lee to discuss shooting The Thrilla in Manila, [a project about Muhammed Ali and Joe Frazier’s legendary boxing clash] in 120fps HDR,” he explains. “I was looking forward to it because I think this is a visual step that has to been addressed. I would love to understand whether 120 can work to tell a story. It does deliver absolute clarity, almost like you can step into the picture. At the same time it means that production design, costume, make-up all need to catch up because it will show any imperfection. You can’t lie with this system.”

“It may be the case that you can play with the speed of different scenes as part of the grammar to storytelling,” he muses. “You could choose to shoot the boxing action at 24 frames and switch between 24, 96 back to 48 or 120 where it suited the story. You could do it subtly such that an audience wouldn’t be aware of what you were doing other than having the scene emotionally resonate with them. That’s my feeling about 3D too - that if done well it can be a subtle enhancement to the narrative and organic to film language.”

Richardson was also lined up to shoot Disney’s live action The Lion King before a conflicting schedule denied him. Like director Jon Favreau’s VFX-Oscar winning smash The Jungle Book, this is being filmed using virtual production techniques – green screen sets with minimal live action elements integrated seamlessly into photoreal computer generated environments and animations.

“I would have loved to have made that film,” he says. “I am really excited by the possibilities of the technology.”

“I began making movies at a time when the subject material was vital, and with directors who dealt with material that meant something… Today, the subject matter for major pictures is less vital than its commercial potential.”

Background and influences

Born in Massachusetts in 1955, Richardson developed an interest in photography while studying at the University of Vermont, but it was films like Lawrence of Arabia, 2001: A Space Odyssey and in particular the work of Swedish auteur Ingmar Bergman (Persona, The Seventh Seal) that altered his perception.

“I dropped everything to concentrate on film. I didn’t feel I was capable or mature enough to be a director but I was fascinated by creating stories and began to appreciate more and more that doing so needed the craft of a cinematographer. I made a decision to go in that direction.”

He joined the film department at the Rhode Island School of Design and continued studies at the American Film Institute [AFI] in LA where he was apprenticed with Bergman’s cinematographer Sven Nykvist and Nestor Almendros, the Spanish DP who lensed the films of French director Eric Rohmer as well as American new wave classics like Terence Malick’s Days of Heaven.

He says being on set with Nykvist shooting Canary Row (1982) and then much later with iconic Bergman actor Max von Sydow on Shutter Island (2010) was like “touching upon the time of gods.”

He had done some second unit work, notably on Alex Cox’s cult classic Repo Man (1984) and several documentaries including one for PBS on the civil war in El Salvador, but in 1985 when gung-ho writer/director Oliver Stone invited him to Mexico, it was both adrenalin rush and gamble. It was first sole DP feature credit.

“On Salvador I really didn’t know a great deal but Oliver and I collaborated intuitively and learned as we went along.”

Immediately afterward they went to the Philippines to shoot Platoon. Both films released in the same year with the controversial Vietnam pic, also shot semi-documentary style, landing the 1987 Best Picture Oscar and Richardson’s first Academy Award.

“We worked on successive films by each putting together our thoughts on the whole script. I would storyboard or shot list the entire script and present it as my thinking and I would get a negative or positive response. We did that for every film, always balance and adjusting feedback from each other, fine-tuning the story.”

When Martin Scorsese asked Richardson to shoot his Vegas-set mob opus Casino, Richardson tried the same approach.

“Before shooting I was called into the production office. Marty said he hadn’t read my ideas and nor was he going to until he was happy with the script. He said, ‘When I’m happy with the script I will give you every shot in the movie [to devise]’. Which he did. This transformed my vision substantially. Here I was responsible for lighting, framing and operating every shot on the movie. This was a massive learning lesson for me and for my crew also.”

It’s worth highlighting his crew, since for three decades Richardson has worked, by and large, with the same key grip, Chris Centrella, and gaffer, Ian Kincaid, and for fifteen years with camera assistant Gregor Tavenner; “They are all masters of their craft,” he says.

Aside from Nykvist he singles out John Alton’s composition and stylised lighting in work for director Anthony Mann in the 1940’s (T-Men, Raw Deal, Reign of Terror) as key influences but it is Vittorio Storaro (The Conformist, Apocalypse Now, Reds, The Last Emperor) who he reveres as the greatest ever cinematographer.

There is, though, one shot of his own making with which Richardson is deeply in love – and it is not one you’d necessarily pick. It’s the final sequence from Platoon, shot from a helicopter as the injured Chris (Charlie Sheen) leaves the hell of Vietnam behind.

“He is looking down, in shock, trying to comprehend the experience of all the lost lives and everything that is destroyed below. This wasn’t a hard shot, technically, but something about it still resonates with me - and not everything does that.”

- Read more Interview: Maxine Gervais, Colourist

- Read more Interview: Hauke Richter, Game of Thrones

No comments yet