The power of archive is dramatically on show in Lionsgate’s Michael Caine-fronted feature documentary My Generation, which traces the cultural revolution that occurred in 1960s England. James Hunt explains how he sourced and sifted through 1600 hours of footage, 500 hours of audio and tens of thousands of still images.

“My job? I have a foot in legal, I have a foot in post, I have a foot in the creative element, and I have a foot in the research and the paperwork, so I’m across all of it,” explains James RM Hunt, the Archive Producer on My Generation charged with pulling the whole film together. “It’s not just about finding footage.”

While there are plenty of feature documentaries that rely on footage to tell their story, few have done it with the verve of My Generation or, indeed, done so with so much previously unseen footage.

Eschewing talking heads entirely, the film relies on narration from Michael Caine — written by British comedy writing royalty Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais — and interviews undertaken with him and many of the most influential figures from the time. Twiggy, Mary Quant, David Bailey, Marianne Faithful… it’s a long list and a stellar one.

Meanwhile, it crams 2,000 cuts from 85 sources into its 85-minute length while it charts the course of the cultural revolution that ignited across England, and in London in particular, during the latter part of the 1960s.

“The wishlist for it was immense,” says Hunt.

“I had a list of characters, times, events, places and things, and literally went through all the archives in the world and tipped them upside down and shook them; mugging them for all their material possible, and not just limiting myself to the stuff that is online.

”If it’s online I’m less interested: I want unseen stuff. I also went to a lot of the interviews, spoke to a lot of people, and they’d tell you to speak to this person or that person to help you track down the footage we wanted.”

“I had a list of characters, times, events, places and things, and literally went through all the archives in the world and tipped them upside down and shook them; mugging them for all their material possible” – James Hunt

Detective work

Some of the anecdotes Hunt tells about tracking down the footage are not only a perfect fit for the freewheeling nature of the decade,but are also a testament to what sheer dogged determination can achieve over the course of a five-year production period.

The end result was a huge mass of material that encompassed 1600 hours of footage, 500 hours of audio, and what Hunt says were tens of thousands of still images.

“How often are you given a lot of money and a lot of time and told to go for it?” he asks rhetorically. “In my job it’s a dream. There are only 11 minutes of BBC and 11 minutes of ITV archive in the film. Most of it has been seen before, but not all of it. A TV doc would have been done in three months: this was five years. It’s qualitative research rather than quantitive — although it became quite quantitive in the end for sure!”

During the production Hunt disappeared down some impressively long and labyrinthine rabbit holes. Director David Batty had read in a book that Robert Amran once made a film called Dolly Story that featured footage of Vidal Sassoon dancing.

“It took me two years to track that down and I had to get all the special skills out (I spent a lot of my own money taking people for drinks as I wanted this to be my magnum opus),” says Hunt.

“I found a guy who had screened it in LA at a mod festival in the mid 2000s. I got hold of him and he said he knew Robert, who I eventually tracked down in New Mexico. Two years later I managed to get it to a screener, and it turned out to have Vidal Sassoon not only dancing but also doing all his signature haircuts in his salon.

”There’s a one-minute section of that in My Generation, which is great as there’s only one other sequence of him doing that in existence and it’s not very good.”

The amount of unearthed material in the film is impressive.

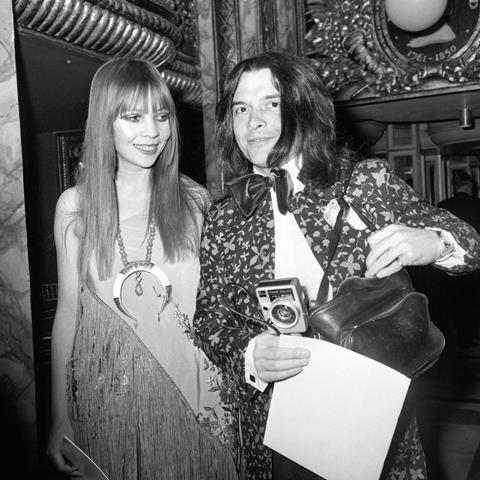

“Three colour specials featuring Twiggy that were broadcast in the US in 1967 were finally found after a long hunt at then producer and boyfriend Justin de Villeneuve’s family home.

CBC in Canada had some amazing stuff. They sent me a log of their material.”

Previously unseen footage of Jean Shrimpton being shot by David Bailey was found in a film can mislabelled as a documentary on bonobo monkeys in the Canadian Broadcast Corporation’s archive.

“Some of the most amazing footage from the film comes from Peter Whitehead, one of the seminal documentary makers of the 1960s,” explains Hunt.

“The footage of Caine being interviewed in the 60s is from his film Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London. It took me years to persuade him to give us an interview, and I asked if he had any raw footage from that film. ‘Yes darling’, he said. ‘I gave a lot of it to the BFI but I still have a whole shed full.’

”He gave us permission to get his stuff out of the BFI and we transferred that and his own material to 2K, the BFI got back the films and the 2K masters, Peter got the same, and we got a load of really fantastic, colour footage of London. We use about 10 minutes of it and it’s great. So much of the material from that time is simply the Establishment saying ‘This is London, look at Carnaby Street’; whereas Peter’s eye behind a hand-held 16mm camera is what it really was like.”

Altruistic work

As well as paying for the footage, My Generation also gave the rights holders back the scenes of their material on LTO5 tape.

“It’s a slightly altruistic way of working,” says Hunt. “But the film might degenerate and I want this to be available for future generations. A lot of the audio reels, the mag reels, are not so robust as celluloid, and they’ve already perished.”

All the material was scanned at 2K.

“We thought about doing 4K, but after I’d been researching the archive for a year we realised that most of the core material was shot in 16mm. We did loads of tests that we projected onto a big screen of a 4K transfer and a 2k transfer, and to be honest with 16mm you cannot tell the different.

”The amount of information on a 16mm frame is four times less than on 35mm, so while you can transfer 35mm to 4K and it looks amazing, with 16 it’s wasted effort. So we settled on 2K, partly because we always wanted to be a big cinema release.”

Even the edit for the film, which was done by Ben Hilton, took three years. They tried it several different ways, including using talking heads, as Batty, Hunt and Hilton tried to work out exactly what the story was. In the end though, ironically the final cut turned out to be very similar to the first one they assembled.

The editing pressures weren’t just narrative either.

“The first cut of it came out so ridiculously over budget, we had to cut it and cut it again until it came into budget,” says Hunt. If you’re careful you can do that without sacrificing any of the major story elements. There was loads of stuff I’d like to have got in it, but we just couldn’t afford it all.

”Feature film clips are generally one of the most expensive pieces of archive in the world, so I had to limit myself to the affordable studios. I didn’t put any material in there from one big Hollywood studio, for example; $30,000 for a minute minimum when you only want three seconds is just not going to happen. Luckily, Caine did most of his films for Paramount and they were a lot more economical.”

Next up for Hunt is The Quiet One, a biopic of Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman, which will also feature some of the 1600 hours of footage he has sitting as proxies on his hard drive.

So, was there anything that his years of research into 1960s London and his mugging of the world’s film and TV archives failed to uncover that he’d like to get in there? As it happens there is: a film about Mary Quant called ‘Youthquake’ made by a US department store.

“I’ve found bits of it in other films but never found the half hour original,” he says. The search continues.

No comments yet