The business of being funny is no laughing matter. Compared to genres like factual, reality and drama, comedy can be too expensive, too regionally specific and just too much of a risk.

There are signs that the comedy industry is struggling to maintain its place as a boom area for the digital era of video broadcasting.

While stand-up comics have turned into rock stars and comedy movies like The Hangover franchise can tickle the funny bones of many millions of people, creating a hit sitcom or any kind of long-running comedy series is tricky.

Filming the live show of the world’s best stand-ups – from Chris Rock to Steve Martin - and sticking them into your schedule or on your streaming platform has been working for about a decade, but it’s a tactic that is starting to appear a little tired.

Recent data from Ampere Analysis reported that Netflix – the platform with more money for content than any traditional broadcaster and a heavy investor in stand-up talent over the last few years – is just one broadcaster with a new comedy strategy. The digital giant is switching its money from comedy, which has done its job in delivering millions of young subscribers, to drama as it seeks the older generation.

“Comedy is still about 17% of Netflix’s original content,” says Richard Broughton, Research Director at Ampere Analysis. “But there has been a definite uptick in drama and sci-fi/fantasy.”

Netflix also says that its subscribers do not want as much comedy any more, according to Ampere, especially as so many stand-up programmes are already on the platform. The thinking appears to be that while the range of funny men and women attracts subscribers, enough is enough.

By contrast, about 15% of Amazon’s catalogue can be categorised as comedy and it has been very active with acquisitions, picking up series such as Seinfeld and A League of Gentlemen. Amazon’s biggest self-made hit so far has been Transparent, the story of a 60-something divorcee announcing to his three grownup kids that he is going to live as a woman, but there are no signs of a similarly successful origination.

In the more traditional broadcasting world, the hot comedy trend of the moment is the writer/performer shows where a strong, talented person creates a world that they then inhabit along with a cast of trusted, similarly funny characters.

Fleabag starring the multi-award-winning Phoebe Waller-Bridge (bought by Amazon) or Detectorists (acquired by Netflix) written and directed by ex-The Office star Mackenzie Crook are fine British examples that began life on BBC3 and BBC4 respectively.

Meanwhile, Atlanta, a semi-autobiographical comedy-drama on FX by Danny Glover is a close US equivalent.

Comedy show executive producer and former BBC Commissioner Simon Lupton says this kind of talent-led comedy is a move away from the classic sitcom which often feels old fashioned in the digital age.

He says: “Comedy makes a promise to the audience in a different way than, for example, drama. It has to move with the times and shows like Fleabag are distinctive and that’s what’s in favour at the moment.”

Lupton, however, says that the TV industry has not yet fully adapted to the new world of broadcasting. “

Drama sells internationally and so gets very big audiences, but comedy now has fewer slots in the schedules, it often has to be found by an audience and there isn’t usually enough time for that to happen,” he says.

Broadcasters like the BBC with feeder channels such as BBC3 (now an online-only viewing option) are in a good position to nurture new ideas.

However, comedy producers are scratching their heads about what to pitch and who to pitch it to.

That’s because the likes of Netflix provide very little guidance, only providing consumption data about new subscribers to larger studios, but nothing contextualised or with any individual focus on a particular show. The stories of Netflix execs immediately greenlighting ideas are true, but many producers need a little more than that simple instruction.

“Netflix and Amazon don’t have a coherent strategy, at least for comedy,” says Lupton. “They never tell you what works; they just say it’s a myriad of things.”

For a comedy producer like the London-based Channel X (which delivered all three series of Detectorists), the Netflix attitude is slightly baffling. “Mostly, it’s single-camera, almost gentle, meandering shows, sometimes quite deep almost bordering on drama,” says Jim Reid, Channel X Director of Programmes. “They look like shows by writers who want to write films and they are designed to be binged on.”

But the need for multiple viewings is not lost by traditional channels as well, including UKTV’s Dave which prides itself on being brave with its comedy commissions. “Our shows, certainly on Dave, should have repeatability and returnability,” says Richard Watsham, Director of Commissioning at UKTV, “so that they achieve strong ratings across many transmissions. We are happy that UKTV original programmes, that repeat on our own channels, do better than those from the BBC, for example.”

A raft of Dave originals has been led by Taskmaster, in which a group of stand-up comics take on a series of ridiculous challenges. With a dedicated comedy channel, Watsham is enthusiastic about the genre: “We doubled down on the success of Taskmaster and there is a huge opportunity in comedy entertainment right now.

“The comedy genre is evolving; there’s lots of nuance nowadays. We are in a period where we de-construct the old structures and engage with talent to build ideas around their thinking. Taskmaster and our latest hit show The Horne Section, for example, were re-versioned from performances at recent Edinburgh Festivals,” says Watsham.

Even for the top comedy writers of the day, the marketplace is equally difficult because risk-averse commissioning usually means every idea has to come with a star name attached or at least as a vehicle for a well-known performer.

Brian Leveson’s credits over the last three decades include My Family for the BBC, The Booze Cruise for ITV and a raft of jokes and sketches for everyone from Russ Abbot to Kenny Everett. He sees lots of problems before comedy reaches traditional television screens, either because of one person’s taste or death by committee.

“Nowadays, a script can go through a dozen hands before there is any possible progress. If a script is liked, a cast is assembled and they stage a reading, essentially turning a TV show into a radio show. But if this goes well, a second script will be commissioned to ensure the first wasn’t a fluke,” he says.

“All stages are scrutinised in committee and by anyone else with any form of interest. They look at demographics and saleability. Yet, it can happen that if one senior person has the slightest hesitation, that’s it, goodnight Vienna.”

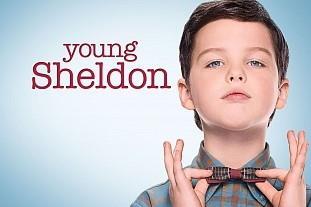

In the US, critics are bemoaning the lack of successful, large audience sitcoms. The Big Bang Theory prequel spin-off on CBS Young Sheldon did not make a big bang when it started last autumn and then there was the rise and fall of the re-boot of Rosanne which was spectacularly dropped by ABC when its eponymous star committed showbiz suicide via a nasty Twitter comment.

This all illustrates the nervousness of traditional networks and does little for writers looking to pitch really new ideas. Leveson’s mantra is “if it ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the stage”, so at least the recent turn towards writer-performers makes total sense because they bring their own ‘star’ quality.

Unfortunately for the comedy community around the globe, the solution to any perceived drought of funny programmes is not the same as it was for the music business – publish your songs on YouTube or some other digital social platform and watch your audience grow until you get seen by a big-time producer. “Lots of writers are getting their mates to film stuff and put it on YouTube, but that’s where it stays,” says Leveson.

But funny is always funny and Jim Reid sees that in some of the new less structured formats. “Shows like Alan Davies: As Yet Untitled looks like it has no structure because it’s a bunch of comics sitting around showing off. But it’s beautifully cast and that’s its strength. There’s a few naysayers about, but I still think it’s a golden age of comedy now – the worry is where comedy will be in 10 years’ time if the SVoD platforms blow the traditional channels out of the water,” says Reid.

No comments yet