Recent developments in TV technology only offer more of the same, whilst Next Generation Audio offers completely new opportunities and a chance to address one of the most frequent causes of complaint made to broadcasters, writes Rupert Brun.

Recent developments in TV picture technology have been rapid but these improvements simply give us more of what we already had. We can offer more pixels, more colours, more pictures per second and more shades of grey.

Developments in the audio side of TV have been even slower. Stereo was invented in 1931 but not widely used for TV until the 1980s with surround sound coming along a decade or so later. Like the video improvements, audio developments have offered more of what we know, delivering more channels, each one mapped to a specific loudspeaker. The quality of the pictures and sound delivered to consumers has increased greatly, and many new platforms have been introduced, but the essential offer is changed.

Next Generation Audio (NGA) is a new approach. NGA isn’t just “more channels”, it offers totally new possibilities. NGA supports the traditional channel-based approach and adds high order ambisonics and audio objects.

Ambisonic sound is popular in virtual and augmented reality applications because of the comparative ease with which the sound stage can be rotated in response to the user turning their head. Audio objects are streams which, unlike channels, are not mapped to a specific speaker for replay. Instead, the audio is accompanied by metadata to tell the receiver what to do with the audio; where in the room to position it and how loud to make it. Crucially the content creator doesn’t send the final mix to the consumer, instead some audio and instructions to tell the receiver how to create the final mix are sent. Delivering some sounds unmixed to the consumer opens a world of new possibilities.

Personalised audio

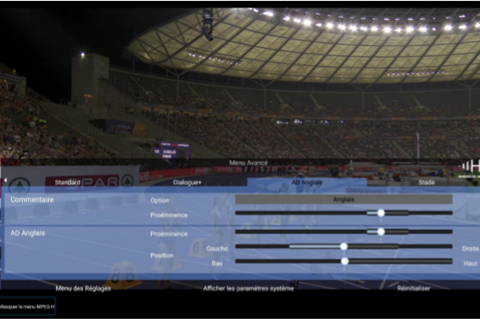

Imagine a broadcaster is covering an athletics championship. It might send the sound of the stadium as a 5.1 bed, as is done at present, but instead of mixing the commentary into this we send it separately with metadata to tell the receiver to render the commentary to the centre of the screen. Additional audio objects can be sent, such as partisan commentary or dialogue in different languages and the viewer can choose between them.

There are two immediate advantages to this approach. Firstly, there is a significant bandwidth saving; each additional commentary requires only a comparatively low bit-rate mono audio stream and a tiny amount of metadata. The bandwidth-hungry 5.1 stadium sound only needs to be delivered once. Secondly the viewer can make their commentary choice through the user interface on their TV or mobile device rather than having to change to a totally different channel or IP stream to hear a different commentary. There are advantages for the broadcaster too; one NGA stream can replace a number of traditional streams because multiple languages can be carried in a single stream.

The biggest impact of NGA will be felt in the area of accessibility. When speech is sent to the receiver as a separate audio object, the viewer can be offered a choice of two mixes, a default mix and another with dialogue boost.

In the UK alone, about 9 million people have some form of hearing impairment. People with hearing loss often find it hard to understand dialogue in the presence of background sounds and dialogue inaudibility is one of the most frequent causes of complaint to broadcasters.

Many factors can contribute to poor dialogue intelligibility, including background sounds both in the mix and in the viewing environment, unfamiliar accents, and speech in a language other than the viewer’s first language. The slim-line design of modern TV receivers with small loudspeakers facing down or towards the rear also presents a challenge to delivery of clear dialogue.

Increasing consumption of video media on mobile devices, often in noisy environments, presents yet another barrier to good intelligibility. Broadcasters could of course make the dialogue more prominent in the mix, but for viewers with good hearing and a home cinema system, such a mix is likely to sound unpleasant, lacking the immersion they expect to enjoy.

“It is clear that diversification of the audience and of media devices mean one mix no longer works for everyone”

In an experiment I conducted with the BBC and Fraunhofer IIS in 2011, a web-based player provided coverage of the Wimbledon tennis championships. Users were able to adjust the sound balance between the court and the dialogue. User feedback indicated two preferred settings, one with some dialogue boost and one with some dialogue cut. It is clear that diversification of the audience and of media devices mean one mix no longer works for everyone.

The boosting of dialogue with NGA increases the prominence of speech in the mix by increasing the gain applied to the dialogue object whilst reducing the volume of other sounds, so overall loudness is preserved. Content creators can further improve the experience by making it possible for the consumer to boost not just the dialogue but also sounds which are important to the narrative, such as an out of vision door opening in a drama. It is also possible to offer the viewer sophisticated controls and allow them to create their own mix, moving objects around the room as well as changing the prominence of different sounds, but it remains to be seen if this is something the mainstream viewer will want to do.

Audio description for the visually impaired viewer is improved by NGA, as the viewer can control how loud they want the audio description to be and where in the room they want to sound to come from. Moving the audio description voice away from the screen can make it easier to understand because it is spatially separated from other sounds. The spatial separation can also make it less distracting for other people watching at the same time who don’t need the audio description service.

The Practical Realities

NGA can be delivered by broadcast or over IP and many receivers already support NGA technologies. In South Korea, the UHD TV service provides Next Generation Audio 24/7 using MPEG-H Audio. So, it’s clear that NGA can be delivered end to end over broadcast and IP platforms. (For more on a recent use of MPEG-H in broadcast, including a successful EBU trial at the European Athletics Championships in 2018, please have a look at the Fraunhofer IIS audio research blog https://www.audioblog.iis.fraunhofer.com/tag/mpeg-h)

Because NGA offers completely new experiences, implementing some of the advanced features requires new ways of working. It is however possible to implement NGA gradually.

A broadcaster or OTT provider might start by adopting the new NGA codecs, which are more efficient, but use them to deliver traditional channel-based audio. The broadcaster can then add options such as a choice of commentary or dialogue boost as and when the business is ready for it, and the business benefits justify it.

There are three competing NGA technologies to choose from. Dolby AC-4 and Xperi DTS:X both grew from developments in the feature film world whilst MPEG-H from Fraunhofer was designed from the outset to support live and recorded broadcast content. Broadcasters may wish to use an open standard such as ADM for production and convert to one (or more) of the distribution formats when sending content to the viewer.

Choice of a consumer delivery format should always be based on thorough practical trials to see how the technology works in reality using your infrastructure and workflows, rather than just listening to the promises and demonstrations made by the sales team. All three technologies offer broadly the same functionality but there are significant differences in the practical implementation and the elegance of the viewer experience.

Does this mean losing control over what the audience hear? Letting the viewer change the sound balance of your carefully crafted programme might at first seem to compromise delivery of the original artistic intent. NGA includes controls to ensure the viewer is only able to change the sound balance in ways and at times the broadcaster has decided, so you remain in control. We all know viewers don’t listen in perfect conditions and if the dialogue is unintelligible, artistic intent is lost.

Allowing viewers in a noisy environment or with a hearing impairment to boost dialogue can enable greater creative freedom, enabling a single asset to deliver the optimum experience to all audiences regardless of the equipment they are using. The ability to offer alternative audio feeds such as a director’s commentary in a drama, or a referee microphone in a rugby match, offer new creative possibilities for those who wish to use them.

A single NGA stream will be decoded by the consumer device to offer the best possible experience, using binaural rendering to give immersive audio with earbuds on a mobile device, all the way through to 7.1 + 4 height in a home cinema. The latest generation of NGA sound bars can give immersive, room-filing sound without the consumer having to fill the room with loudspeakers. Allowing the receiver and consumer to adjust the balance according to the replay environment and needs of the listener may well result in something closer to the original artistic intent being perceived by the viewer.

-

Rupert Brun is an audio consultant and former head of technology at BBC Radio. He received the BBC Radio Gold Award in 2015

No comments yet