Niantic says Harry Potter: Wizards Unite will bring unprecedented scale to AR gaming. It could also provide a glimpse into the future of entertainment.

The company which jump-started consumer AR with the phenomenal hit Pokémon Go is back with a Harry Potter-themed game which promises to be the first real-time synchronised multi-player augmented reality experience.

It is primed for the introduction of 5G and could be the killer app which operators and handset makers need to get consumers to buy 5G smartphones and network subscriptions.

But the ambitions of its developer go far beyond simple gameplay.

The “planet-scale augmented reality platform” which underpins it is intended to function like a global operating system for applications that unite the digital world with the physical world – or as Niantic’s John Hanke puts it – uniting holograms with atoms.

“We stand at the beginning of a whole new era of augmented reality experiences and a new digital interaction for information and entertainment,” the company’s founder and CEO said at Mobile World Congress in February.

“Yes, it is being hyped, but a paradigm change like this happens maybe once every couple decades.”

“We stand at the beginning of a whole new era of AR experiences”

Pokémon Go has achieved over 2 billion downloads. The company’s vision and track record have valued Niantic at almost $4 billion, propelled by investors including Samsung Ventures and esports group aXiomatic Gaming.

- Read more: Analysis: What does the future hold for VR?

It will be hoping for more of the same mass participation when it launches Harry Potter: Wizards Unite, made with the blessing of Warner Bros. and JK Rowling, later this year.

The title is built using an inhouse gaming engine “that allows hundreds of millions of players to play in a single global instance,” Hanke says.

Pokémon Go, which is built on this platform, has already demonstrated concurrent real-time usage of several million players in a single, consistent game environment, Niantic says, with demonstrated monthly usage in the hundreds of millions.

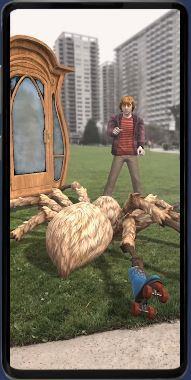

But the AR Platform, for which Harry Potter: Wizards Unite is the first application, is of another order entirely. With it, the San Francisco-based outfit aims to solve a number of the key limitations of current AR. Ideally, AR objects should be able to blend into our reality, seamlessly moving behind and around real-world objects in real time.

To tackle this, Niantic is using machine learning to determine the depth of every pixel in a video frame and then applies that to make virtual objects obey real world physics.

What’s more it is using the same pixel depth data to map every physical location of every user on earth for AR experiences potentially involving billions of people.

If successful it will challenge both Apple and Google’s efforts to establish a monopoly in the emerging AR field.

How? To begin with it’s worth knowing that Niantic was a start-up within Google that helped build apps that became Google Maps and Google Earth before being spun-off in 2005 with Hanke at the helm.

He is taking a similar contextual mapping approach so that animated objects and characters (a Quidditch ball, a wand or a fantastic beast, say) are visible at the same time, in the same place and continuously in time to anyone with the app on their phone or with AR glasses.

“That means we have to photograph and analyse a user’s immediate environment and their positional data to create an AR map in the cloud and serve it back to share with other users.”

Understanding the AR world

Niantic’s AR is an attempt to move from computer models of the world centred around roads and cars – like Google Maps - to one centred around people.

To help with that it is using a dataset submitted, curated and updated over the past six years by players of Pokemon Go which it is combining with other datasets to build contextual computer vision.

According to Niantic, such advanced AR requires an understanding of not just how the world looks, but also what it means: what objects are present in a given space, what those objects are doing, and how they are related to each other, if at all.

“Once we understand the ‘meaning’ of the world around us, the possibilities of what we can layer on is limitless,” it explained in a blogpost. “We are in the very early days of exploring ideas, testing and creating demos. Imagine, for example, that if our platform can identify and contextualise the presence of flowers, then it will know to make a bumblebee appear. Or, if the AR can see and contextualise a lake, it will know to make a duck appear.”

Niantic has the financial resource to code and acquire the tech to do this. In November 2017, it bought Evertoon, a start-up exploring digital social mechanics. In February 2018, it acquired mapping and computer vision specialist Escher Reality and followed that last June by adding London-based start-up Matrix Mill.

This is now Niantic’s London office where Matrix Mill’s trio of neural scientists – all with a shared University College London background - are using computer vision and deep learning to develop techniques to understand and contextualise the 3D space from information culled from the smartphone cameras of game players.

As Hanke puts it, “the larger the vocabulary, the more understanding we have, and the richer the AR on our platform can be.”

A prototype virtual dodgeball game Codename: Neon was developed last year to test the company’s contextual computer vision where AR objects understand and interact with real world objects or people. For example, players in the game can harvest energy from white pellets on the ground, and those are a shared resource–so if one player gets them, the other players can’t.

“All the action, firing, dodging and absorbing of energy is shared with all other players at a very low level of latency,” says Hanke.

Lagging behind

Another internal experiment, Tonehenge, encourages people to work together to solve intricate Myst-like environment puzzles.

Some of the features of these games will reappear in Harry Potter: Wizards Unite.

The other Achilles heel of AR is the latency of data being sent over the network in response to user actions. It’s nearly impossible to create a shared reality experience if the timing isn’t perfect – but 5G solves this.

“With 5G we can get near to instantaneous tens of milliseconds [of latency]”

“Even good latency times today are 100 milliseconds. With 5G we can get that to a near instantaneous tens of milliseconds,” Hanke said.

To put this in perspective, with rendering at 60fps, each new image is displayed at less than 16ms. According to the company, this means that in a peer-to-peer multiplayer AR game you can see where your friends actually are rather than where your friends were.

The company’s cloud-based platform is designed to make it easier for other developers to create AR apps which can run on any device, unlike Apple’s ARKit and Google’s ARCore, which are both focused on their own iPhones and Android smartphones.

Modelling a ‘people-focused’ world of parks, trails, sidewalks, and other publicly accessible spaces still requires significant computation. The technology must be able to resolve minute details, to specifically digitise these places, and to model them in an interactive 3D space that a computer can quickly and easily read.

This is enabled by mobile edge computing in which the processing power is moved closer to the user – at one of the millions of new 5G cell sites being installed - and allows Niantic to perform compute intensive work such as arbitrating the real-time interactions of a thousand individuals playing in a small geographic area.

It has partnerships with Deutsche Telekom, Korea’s SK Telecom and Samsung.

“If you want to build compute intensive shared AR experiences, we need the next level of network,” Hanke says.

All of this presupposes a future of ubiquitous wearable computing, one in which the augmented reality experience is inherently shared and social.

If that’s to work, Niantic believes the AR interaction must feel natural to our senses. “The digital would obey similar rules to the physical in order to create the suspense of disbelief in our brains,” explains Diana Hu, formerly of Escher Reality now Niantic’s head of AR Platform.

For example, in Pokémon Go when it rains in a player’s location in the real world, that is reflected in the game.

Last year Niantic launched a contest for developers to share ideas and build new experiences on Niantic’s platform. The winner stands to receive one million dollars and will be announced later this year.

“It’s all about unleashing the power of indie developers,” Hanke says.

In Niantic’s world, our everyday experiences are enhanced by hardware that is unobtrusive, can go anywhere, and is connected in real-time with low latency 5G connections.

A similar - even rival - concept for mixed reality spatial computing at scale is being imagined by Magic Leap.

It will be interesting to see if and when those worlds collide.

No comments yet