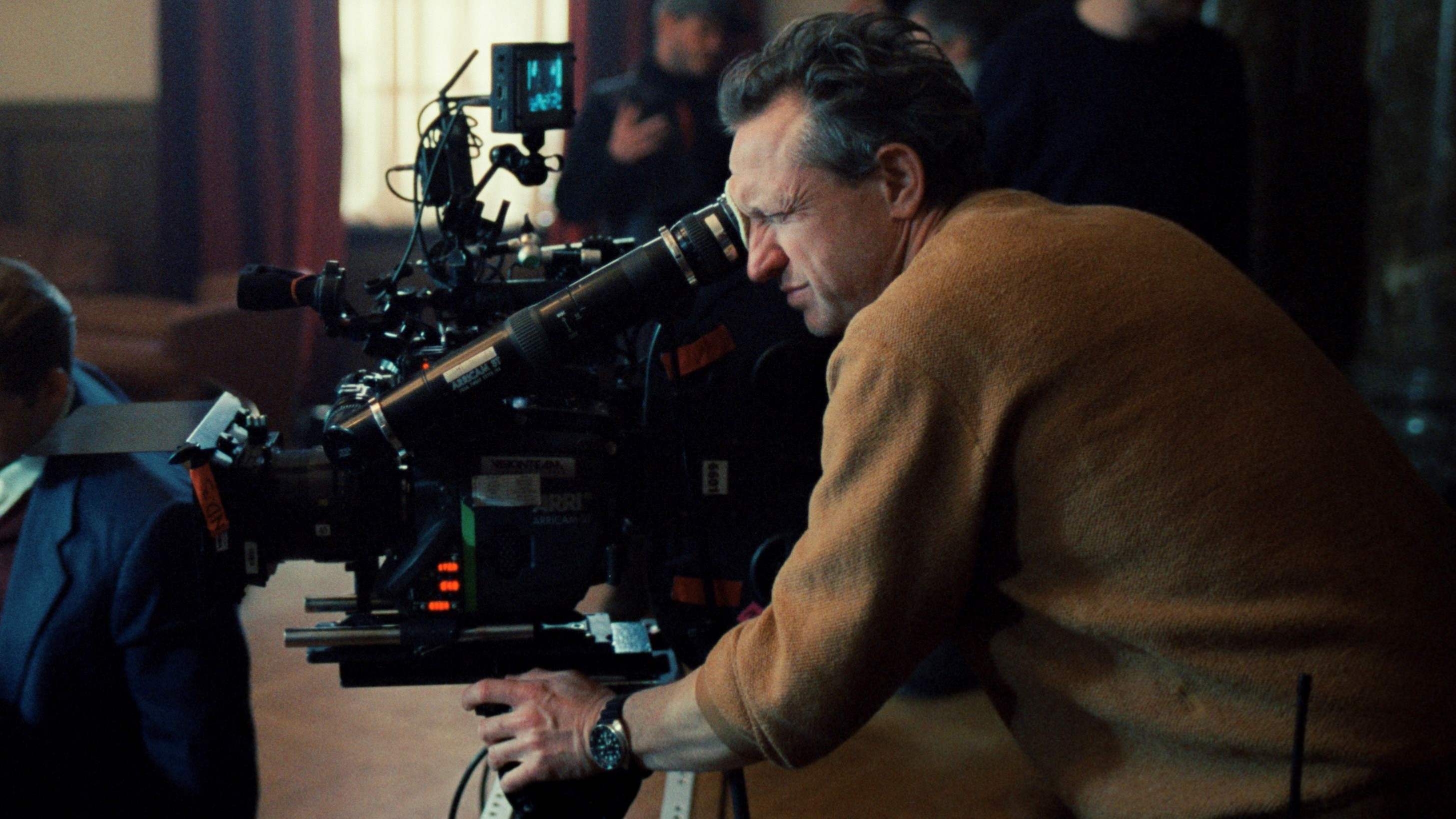

In Alex Garland’s action thriller cameras are a weapon of truth, writes Adrian Pennington.

There’s a scene in Oliver Stone’s 1986 movie Salvador about the country’s chaotic civil war where a photojournalist played by John Savage is killed in the heroic attempt to capture the money shot - or proof - of military bombs falling on the civilian population.

The heroic nature of photojournalists and the wider importance of upholding the journalistic quest for truth is Writer-Director Alex Garland’s mission in Civil War - although the lines are blurred. The film’s hero, a veteran war photographer, is among a press pack dreaming of the ultimate money shot: the capture or execution...

You are not signed in.

Only registered users can view this article.

Behind the scenes: Squid Game 2

The glossy, candy-coloured design of Squid Game is a huge part of its appeal luring players and audiences alike into a greater heart of darkness.

Behind the scenes: Adolescence

Shooting each episode in a single take is no gimmick but additive to the intensity of Netflix’s latest hard-hitting drama. IBC365 speaks with creator Stephen Graham and director Philip Barantini.

Behind the scenes: Editing Sugar Babies and By Design in Premiere

The editors of theatrical drama By Design and documentary Sugar Babies share details of their work and editing preferences with IBC365.

Behind the scenes: A Complete Unknown

All the talk will be about the remarkable lead performance but creating an environment for Timothee Chalamet to shine is as much down to the subtle camera, nuanced lighting and family on-set atmosphere that DP Phedon Papamichael achieves with regular directing partner James Mangold.

Behind the scenes: The Brutalist

Cinematographer Lol Crawley finds the monumental visual language to capture an artform that is essentially static.