Girls with money, men with power. A group of fun-loving young American girls explode into the stiff upper lipped London season of the 1870s, kicking off an Anglo-American culture clash in Apple TV series The Buccaneers, reports Adrian Pennington.

The ensuing drama is played out to a soundtrack featuring female musicians from Taylor Swift to Olivia Rodrigo. “There is the intent from ground zero to reinvent the genre and let it cut loose from the corset strings of period drama tropes,” said Oliver Curtis BSC (Netflix’s Stay Close) who helped design the show look and shot episodes 1 and 2 with director Susanna White (BBC’s Bleak House). “It’s about a collusion of attitudes and sensibility which, from a stylistic point of view, could take you in lots of different directions.”

Inspired by Edith Wharton’s unfinished final novel of the same name, from series creator Katherine Jakeways, the eight-part drama is produced by Forge Entertainment and stars Norwegian actresses Kristine Frøseth and Alisha Boe with Mia Threapleton and Christina Hendricks (Mad Men).

Curtis had not made a period drama since...

You are not signed in.

Only registered users can view this article.

Behind the scenes: Squid Game 2

The glossy, candy-coloured design of Squid Game is a huge part of its appeal luring players and audiences alike into a greater heart of darkness.

Behind the scenes: Adolescence

Shooting each episode in a single take is no gimmick but additive to the intensity of Netflix’s latest hard-hitting drama. IBC365 speaks with creator Stephen Graham and director Philip Barantini.

Behind the scenes: Editing Sugar Babies and By Design in Premiere

The editors of theatrical drama By Design and documentary Sugar Babies share details of their work and editing preferences with IBC365.

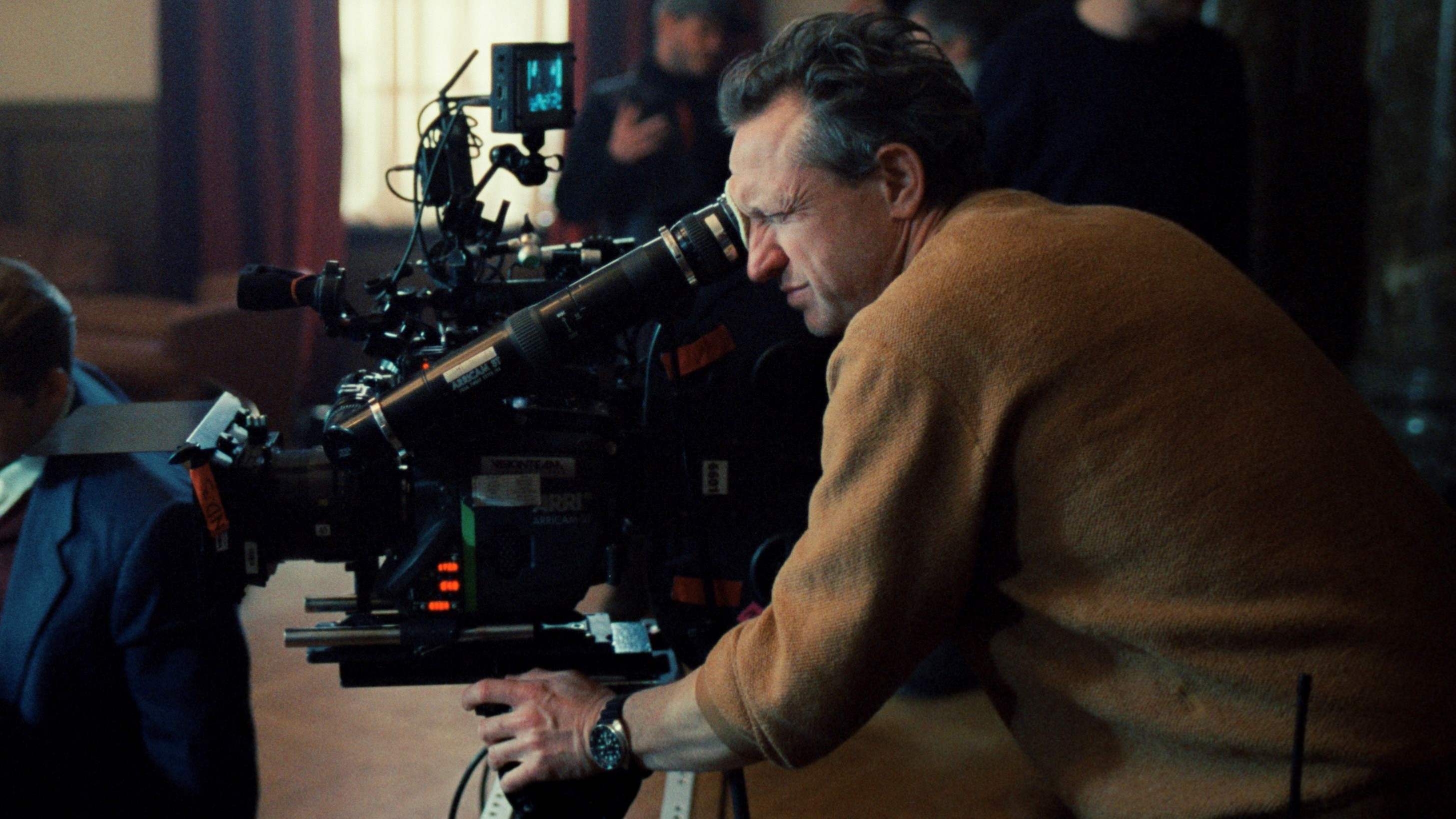

Behind the scenes: A Complete Unknown

All the talk will be about the remarkable lead performance but creating an environment for Timothee Chalamet to shine is as much down to the subtle camera, nuanced lighting and family on-set atmosphere that DP Phedon Papamichael achieves with regular directing partner James Mangold.

Behind the scenes: The Brutalist

Cinematographer Lol Crawley finds the monumental visual language to capture an artform that is essentially static.