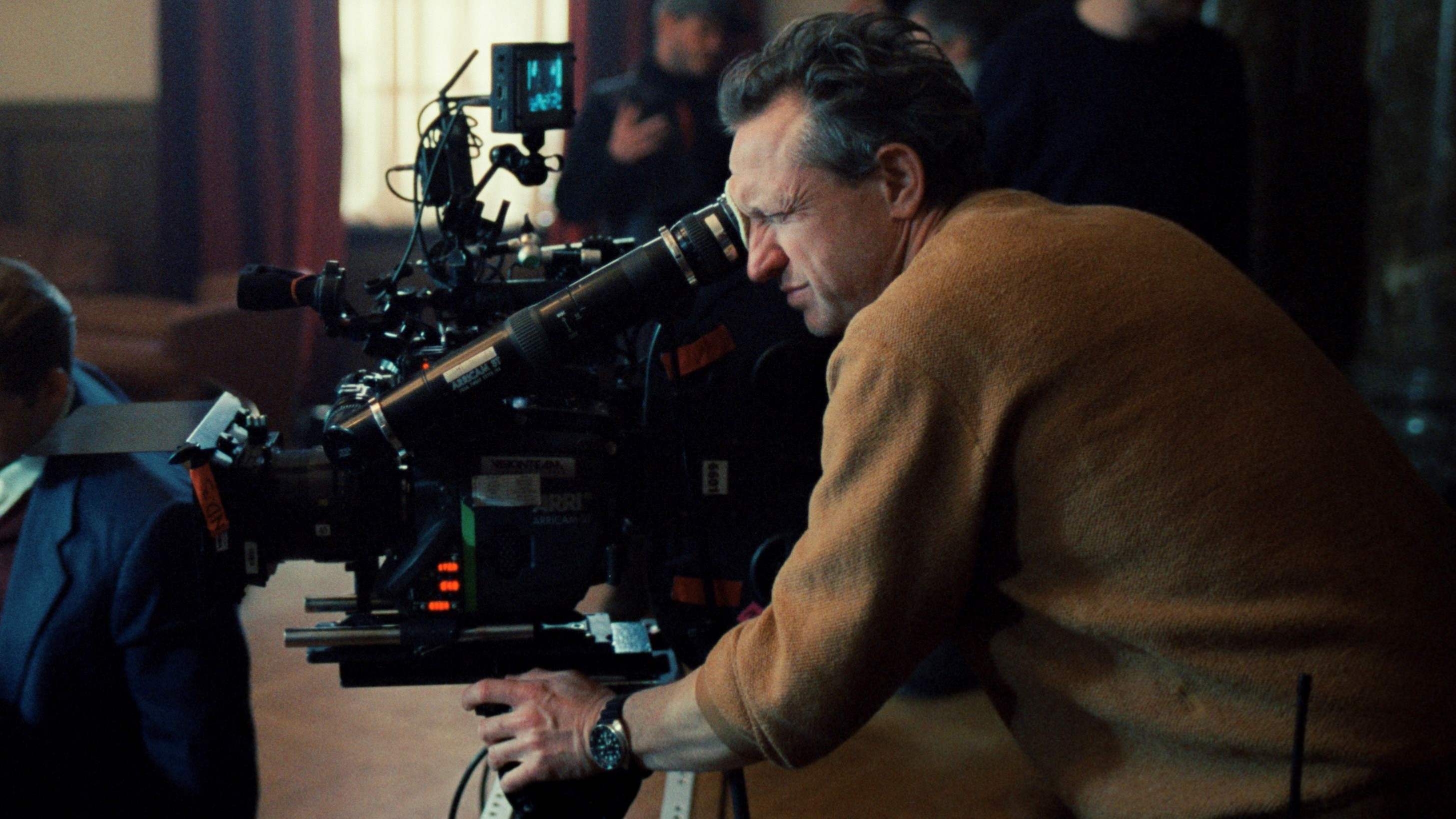

Cinematographer Paul Guilhaume explains how a transgender cartel musical is told with magical realism.

You are not signed in.

Only registered users can view this article.

Behind the scenes: Squid Game 2

The glossy, candy-coloured design of Squid Game is a huge part of its appeal luring players and audiences alike into a greater heart of darkness.

Behind the scenes: Adolescence

Shooting each episode in a single take is no gimmick but additive to the intensity of Netflix’s latest hard-hitting drama. IBC365 speaks with creator Stephen Graham and director Philip Barantini.

Behind the scenes: Editing Sugar Babies and By Design in Premiere

The editors of theatrical drama By Design and documentary Sugar Babies share details of their work and editing preferences with IBC365.

Behind the scenes: A Complete Unknown

All the talk will be about the remarkable lead performance but creating an environment for Timothee Chalamet to shine is as much down to the subtle camera, nuanced lighting and family on-set atmosphere that DP Phedon Papamichael achieves with regular directing partner James Mangold.

Behind the scenes: The Brutalist

Cinematographer Lol Crawley finds the monumental visual language to capture an artform that is essentially static.

.jpg)

.jpg)