Live Production

Live Production

IBC Show VOD

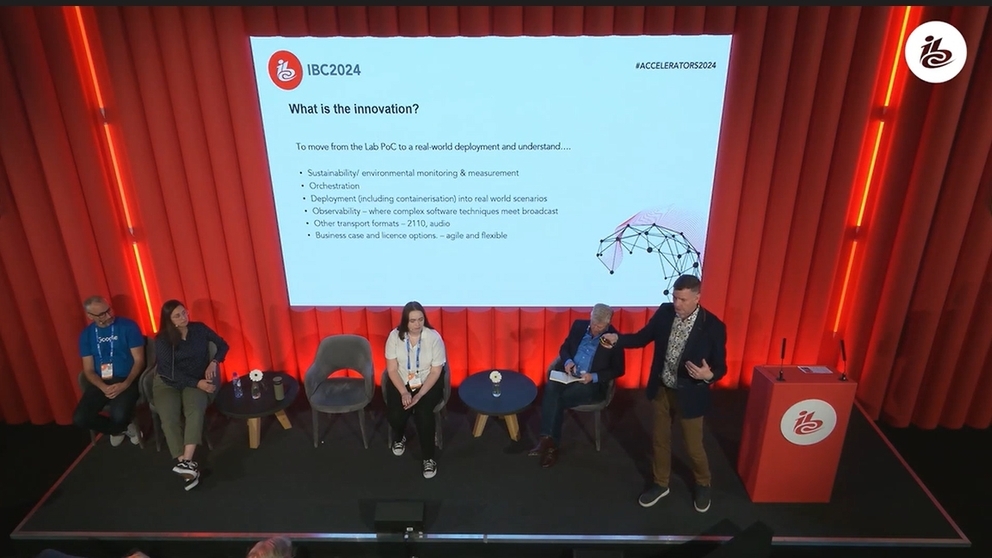

IBC Accelerators: “Seeing it work and seeing the future possibilities for Live Performances made it all worthwhile”

IBC Show VOD

Media Production without Boundaries: “There’s a lot of cool stuff we could do but why should we do it.”

IBC Show VOD

Media Production without Boundaries: We need to pull together to make these ‘interesting times’ work

IBC Show VOD

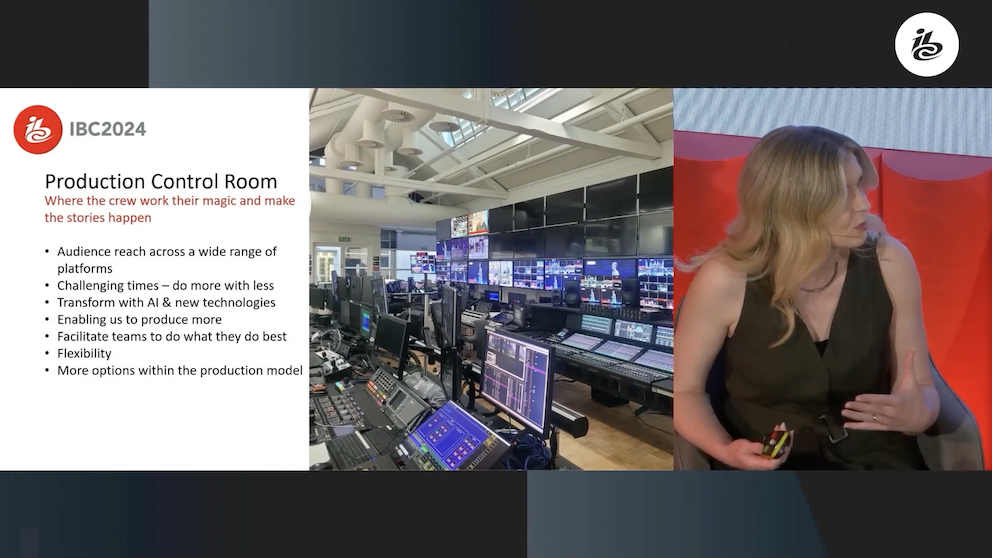

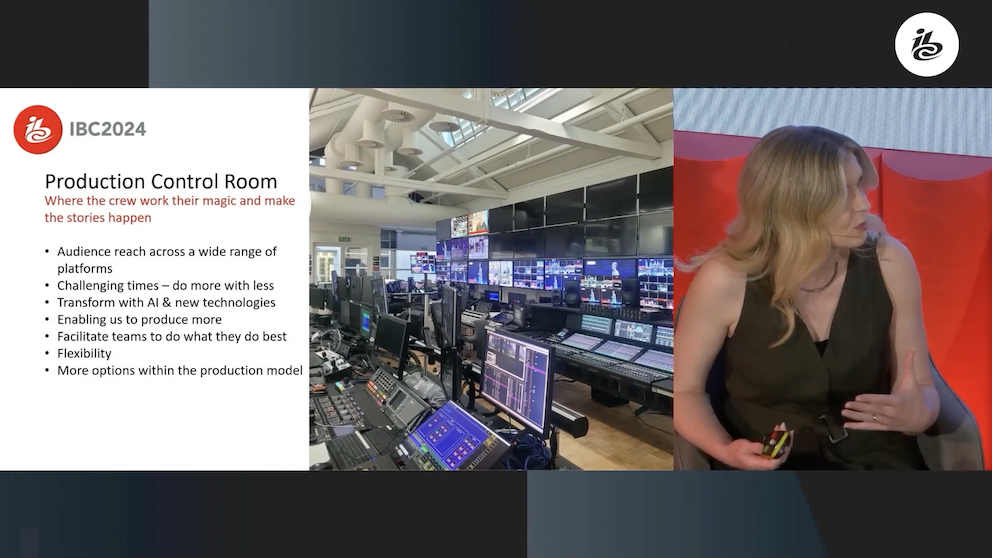

Accelerators - Evolution of the Control Room: helping content creators to produce a show “without advanced technical expertise”

IBC Show VOD

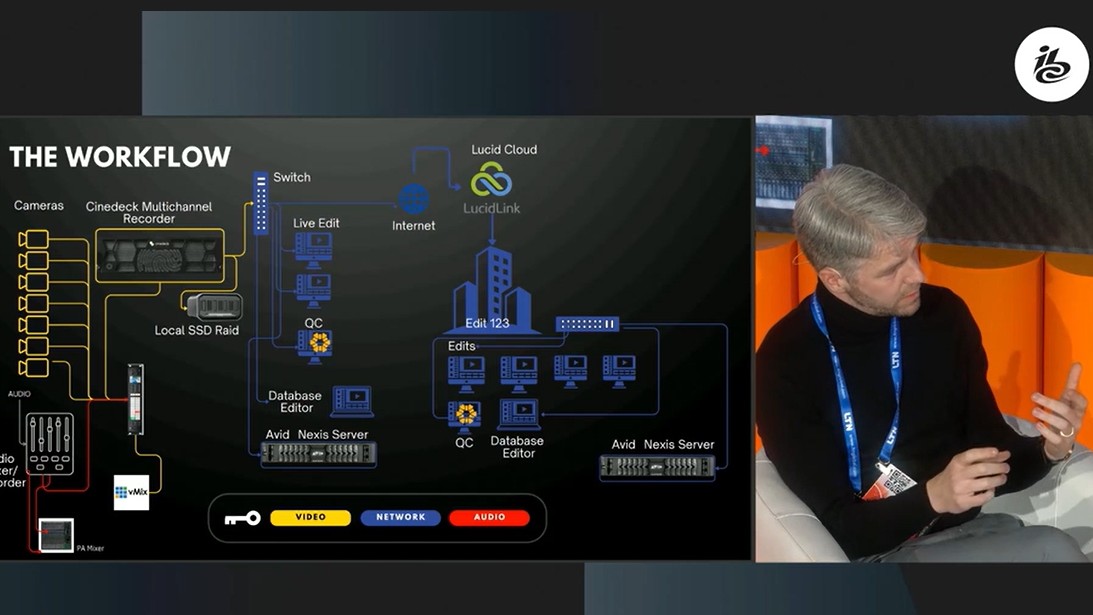

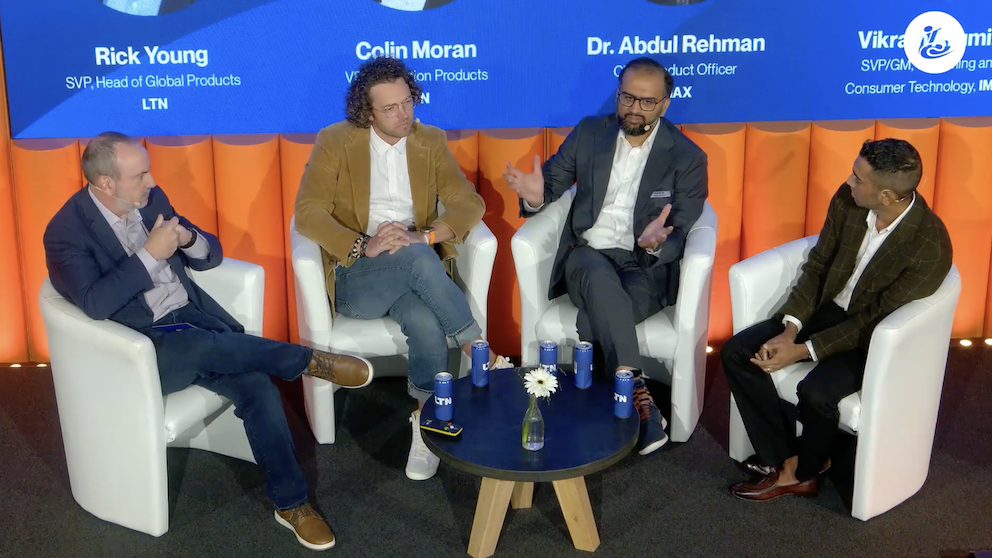

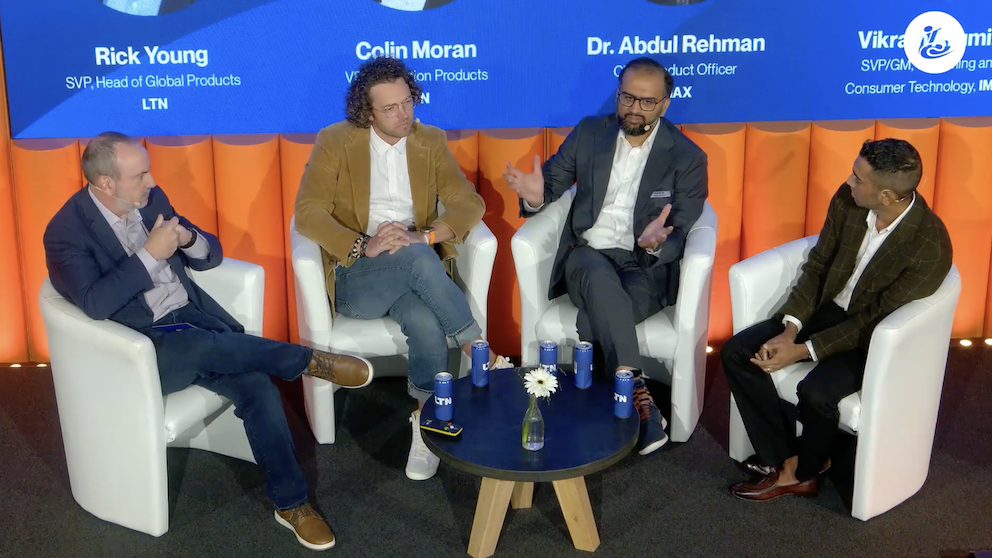

From Paris to Hong Kong: How LTN and IMAX stream the biggest live events to global audiences with theatre-grade quality

IBC Show VOD